Miguel Aguirre

El buen Fausto

Good Old Fausto

The Present in Memory or love in snapshots

Mendel, the second solo show of Peruvian artist Miguel Aguirre, revolves around the family nucleus in general and for this purpose he takes his own as object of observation, analysis and visual experiment. It is fundamental to pinpoint that for Aguirre this nucleus is outlined according to his reading of Latin-American, and particularly Peruvian, socio-psycho-biological experience, specifically of Lima´s middle class. That is why it includes the entire branching complex that involves the members of successive generations within the family´s structure. Essentially produced by marriage with individuals that belong to other family nuclei and yet remain members of their own families as such, they also serve to broadly differentiate a Latin cultural attitude from an Anglo-Saxon one (in the latter the minimal family nucleus has very little cohesion while the extended family as described above is a ghost unit).

This approach to his family nucleus in the form of visual statements could have for Aguirre the tenor of a project in domestic anthropology or visual socio-psychology. However, the scope of his proposal does not adhere to research design in these areas and finally does not correspond whatsoever to specific categorizations. Even though we can say that Aguirre´s procedure, occasionally, verges upon the scientific method, either in pure or social sciences, these instances occur given that the devices or instruments of research have a visual and semantic resonance that draw his attention. And being particularly meaningful for him, they incite him on to a free transposition.

The spatial materialization of this statement is radically related to the materiality of the exhibited works. Mendel has concretely the nature of an installation of works made in different media. The whole is made up of parts that are creations fashioned to contrast one with another and which are taken to a level of friction amongst themselves. This reveals the neo-conceptual aspects of the proposal. In short, it is a multiple inquiry into the representation of the family using different systems and conventions.

Taking as starting point colour pictures, non-professional snapshots, usually taken with cheap cameras -even disposable ones- that are appreciated at home because they keep the memory of happy moments alive forever, Aguirre gives a meaningful twist to the family photograph in a domestic setting, certainly the most extended use given to the photographic medium around the world at the end of the 20th century. As cultural practice, domestic photography surely surpasses by far the contemporary aesthetic practices that make use of photographic medium as well as so-called art photography, a trend aspiring to photographic purism that today is frequently contested. This explains why nowadays many artistic proposals are developed on the basis of an aesthetics derived from the family snapshot -through choice of photographic instrument and of image framing device; or, on the other hand, they are based on the use of family snapshots by direct appropriation or by transposition, by means of digitalization or big printing without any alteration (in the latter options authorship of the images themselves is secondary).

The artist focuses his attention on yet another type of photographic images; these are the formal black and white or colour pictures, taken by portrait studio photographers that capture family members, individually or in small groups, in circumstances defined as milestones in the lives of middle and upper class individuals in our society. At a local level these photographic milestones are: baptism, first communion, graduation party, university graduation, registry office and/or church wedding (portrait of the bride taken in a photo studio), family group (father, mother, children), Silver, Gold and Diamond Anniversaries (with the portrait of the family group in its entirety). In the last century, photo studio practice attended to frequent requests of portraits of the deceased at wakes and funerals. We, at the end of the 20th century, have eliminated the dead from commercial portrait photography.

For Mendel, Aguirre has chosen to work only from photographic images of his family or, shall we say, of the family of which he is a member and which comprehends, besides his parents and his brothers and sisters, a contingent from the father´s line and another from the mother´s line, headed by the grandparents on both sides, followed by the uncles and aunts, their spouses and children. He also proves to be perfectly aware of the fact that one is born in a family, one is incorporated into a pre-existent order that fleetingly seems to acquire the appearance of a dictate of nature for the individual sensibility. This awareness is what allows him to act with responsible liberty in the serious game of observing his family and observing himself within it: processing an image of his family before the gaze of whomever is willing to see.

It is important to emphasize the fact that the artist uses the family snapshot and the photo studio portrait taken by professionals just as starting points in his work and under no circumstance does he appropriate them directly. He works at transformation and at re-signifying these types of images in three series included in Mendel. In the three he concentrates on the manipulation of the photographic images by means of computer software (Photoshop). Through this procedure he can alter photographic reality, while putting to the test the potential of software for the creation of photographic verisimilitude and leading us on to question our trust in the truthfulness of the images. Obviously, he obtains results in which the operations of insertion of elements previously non-existent in the image leave (almost) no trace of manipulation, restoring a natural history -from the genetic code on towards a sense of almost cosmic order- tacitly assimilated and indelibly recorded in his memory. But with a difference: while re-living it, he inscribes himself in it again, sometimes literally and sometimes by interposita persona, transforming the visual with his own commentary and reflection in the visual mode, too. The text that the images in succession effectively write is subtly but definitely altered by him, in his own image, in order to visually represent what is his and his only: that is, his own version of his family.

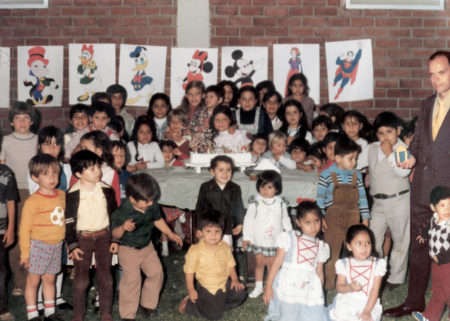

El buen Fausto (Good Old Fausto) is a series based upon the manner in which the amateur snapshot consecrates all celebrations and occasions, big and small, in the life of the family and also on how changes in the structure of the latter are gradually and, to a large extent, spontaneously documented throughout time, in mounting a photo album. The artist enhances this temporal dimension by manipulating the images in order to insert in the family fabric an invented and visually strange element, to which he confers a double role: as a pointer along an implied time-line and as a symbol of continuity of the family rituals. A succession of fixed cyclic events that are easy to imagine going on and on, per secula seculorum, with other different actors of the same blood.

In this case Aguirre resorts to a special character (created by means of especially taken images of a personal friend of his, for this very purpose), not related to the family nucleus by blood, but whose presence is dear to it: the family friend, almost consubstantial with it. This character called Fausto appears physically identical throughout twenty-seven years of family snapshots. Once singled out and recognized by the observer, his presence, his person points to the time of each picture and it renews and communicates a sense that grows from an initial complicity between artist and observer in order to allow the latter to get the most bewildering glimpse of that which is eternal in a family. El buen Fausto reveals itself to be a double allegory of agape -fraternal love- and of time.

Another series, Luna de miel (Honeymoon), has ostensibly as its subject the wedding trip of a newlywed couple to different places in Latin America. Among them one can easily recognize Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, cities that acted as immediate magnets for the middle-class professional who wanted to mark this moment in a special way. It is essential to remember that in its origin, the honeymoon is ritual voyage in which, even though it is important to know the destination, it is even more important to fix its duration since it has to do with starting upon a life in which closeness to the partner as significant other is almost absolute. So, it could be defines as the short or long period -it does not matter- that a couple recognized by the Law or by the Church or both, has a «right» to enjoy in order to generate its intimacy at all levels, an foundation of intimacy proper to newlyweds, which as far the social group´s expectations go, it points to the future origins of a new family.

In every honeymoon photo album, the idyllic intimacy of the couple is photographically signified quite clearly. In societies where the free union between man and woman is not recognized by the Law -therefore, not fully by society- the social charge of the photographic images belonging to the newlywed couple increases, inasmuch as they contribute to naturally establish, in a visual document, its legitimacy and solidity. They are a witness to the adequate constitution of the couple.

In fact, the honeymoon is less a trip to some place than a trip with someone. As attractive as the visited places may be, they are just a backdrop for a new kind of rite. His or her loving gaze is always framing a portrait of the other, for which reason husband and wife appear alternately in the pictures and a circle is completed in every shot since the one has eyes only for the other, to use a cliché phrase: the one who is behind the camera and the one who is front of it engage in a rite that ostensibly involves a strange apparatus but which, in actual fact, takes place at the expense of the apparatus and of photography. Although, in the end, the pictures remain, one could just as well have done without the camera and the film in it. Curiously enough, when husband and wife appear together in the honeymoon photo album, it is because somebody has granted their request of focussing the lens on them and pressing the button. Thus, whoever takes the picture becomes an involuntary witness.

It could be said that these images are rather for the use of their descendants, for whom the interest -and fascination, too- resides in their attempt to project themselves imaginatively to a time past, prior to their procreation and arrival into the world. For the couple itself the images will be just an indicator, a reminder of a moment whose dimension eludes the image themselves, that nonetheless, can be revived by remembrance of the photographic ritual and the conditions in which it took place; it then reveals itself to be a method for the one to become fixed in the memory of the other, in the first moment of erotic intensity as an officially constituted couple.

In different scenes of Luna de miel an unexpected presence shows up: it is a tall young man, about 25 years old, who appears sometimes beside the young wife, sometimes beside the husband, and in other cases with both of them. He is apparently a welcome companion, although the observer can perceive him, from time to time as an intruder in the visual enjoyment of the imagined perfect intimacy of the couple. A narrative can even originate from his presence: it is a possibility that the young man could be the one who took the pictures of the couple during the tour. It may be that the photographer-witness was him, no stranger to them.

This travel companion, smiling and relaxed, appears to have a place within the same halo of happiness that surrounds the newlyweds, with no opposition from them. They would not do it, besides: for their young man is the eldest son, Miguel Aguirre, twenty seven years after the trip, who has inscribed himself in the photographic space of images that condense the honeymoon of his parents. He is the author of this story in images of which, for obvious reasons, he could never have been the actual one and, in a double allusion, that elegantly resorts to autobiographical objectivity and humour, he is also the actor: in this division of himself in two -with pre and post natal implications- he turns his gaze to the possible moment of his conception and, through art, returns not only as the author of his days but as author of his parent´s days.

Bouquets, the last of the series, comprises a group of formal portraits of bride and groom, posing before and after the wedding ceremony -mainly in church but in one case at the registry office- taken mostly by professional photographers. The artist introduces a character in an operation comparable to prior ones. This time is the bride´s little flower girl (related to the artist by kinship), possessed of an innocent and amused smile, who like Fausto in the first series, accompanies a succession of brides and grooms on their wedding days in the last thirty-five years. The variety of shots covers the usual range offered by photographers: portrait at the church or chapel; in front of the altar; portrait by the car that will take them away on honeymoon; portrait in the gardens of the church; portrait at the parish reception room before and after receiving greetings from friends and acquaintances; portrait at the registry office. The only informal portrait does not appear to have been taken by a professional photographer, besides. However, its presence outlines a questioning of the union of man and woman in the face of social trapping. Is the couple less real without the image of church or registry office wedding?

The observer´s feeling of revisiting the past is perhaps more strongly emphasized in Bouquets, precisely because both the formal portraits as well as the visual signs that make the occasion unique -like the bride and groom´s clothes or their hair styles or the bride´s make-up- are characterized by the prevailing taste, they are subject to fashion. This aspect it essentially amusing inasmuch as we can place in time each portrait worked by Aguirre: the picture in every case is the codified record of a period, allowing a study of consensual, socially stipulated sensibilities.

Ever since it was announced to the world, photography was put to uses as diverse and opposed as serving for scientific (and pseudo-scientific) purposes and embodying artistic aspirations; with the emergence of instantaneous photography as widespread, non-professional practice -thanks to George Eastman- an everyday-domestic use was added to the above: it quite possibly satisfied some affective needs and; paradoxically, created others, at the same time.

This last aspect prompted Miguel Aguirre to take a course of action: but the three series developed on the basis of specific photographic material as part of Mendel, far from being nostalgic journeys to the past, are pure affirmation of the author´s place in the present, as a Peruvian man at the end of the 20th century, who is a member of a middle class family. The visual construction he has undertaken culminates in an elevation of affective significance, persuading us that it is the law that rules over all. He has devised an allegory of human continuity by a procedure that it occurs to me to be comparable to the endless editing of genetic material for living: through cutting and splicing of fragments with amazing accuracy, a supreme continuity is maintained from generation to generation.

Jorge Villacorta Chávez

Lima, November 1999