Miguel Aguirre

Before/After

Apocalyptic and disaster movies have undergone a continuous revival during the past 30 years and belong to today’s most popular films. We believe the genre’s solid condition attributable to multiple factors. Its spectacular and dramatic appeal as well as much improved digital effects allow the production of secure box-office hits at the highest technical levels. Despite the origins in the Cold War context of the nineteen-fifties, it has been in recent years that an abundance of films has caused a universalization of doomsday and end-of-the-world storytelling. The rise of the genre is symptomatic for an obsession with the imagery of apocalypse which seems to be ever more frequent in our cultural universe.

The fixation on end-of-the-world scenarios and their consequences is by no means a new phenomenon. From the Book of Revelation to Millenarianism to zombie movies, the eagerness of occidental culture to narrate the how and why of its own destruction can be traced back over more than two millenniums of Judeo-Christian tradition. However, the proliferating success is fundamentally related with a rather recent notion of living in societies that, though safe and secure, are threatened by a disaster which—a key factor for explaining this perception—is accepted as an imminent and inevitable reality. The threat is usually of complex and vague nature and responds to a number of conflicts, problems and challenges that put society as we know it into jeopardy.

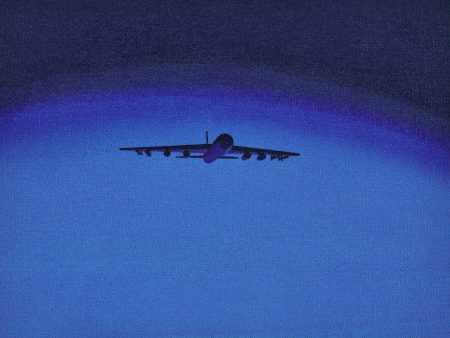

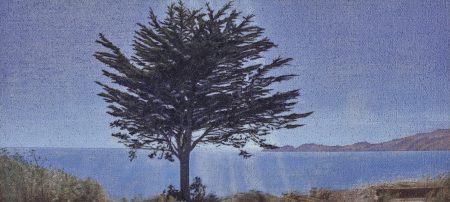

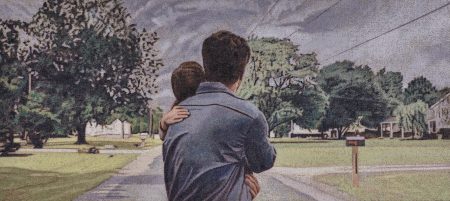

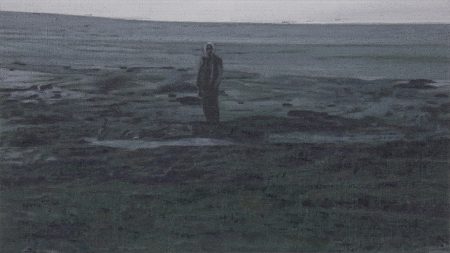

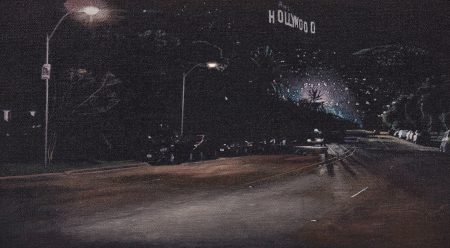

Our project aims to reflect on this conception of the end of the world as part of today’s cultural codes, particularly of apocalyptic and disaster films. In view of the scope of the question we decided for a specific analysis of the extensive visual enrichment brought to contemporary culture through apocalyptic movies since the fifties. To this end we examine the filmic adaptation of landscape and its relationship with the work of several painters of Romanticism. This may deem an arbitrary association, yet to us many movies seem, deliberately or not, inspired by the aesthetics of artists like Friedrich, Goya, Delacroix, or Géricault.

The proposal is simple: 20 films, 20 sequences, each showing a landscape either destroyed and devastated, or just (maybe only seconds) before the catastrophe. Through the translation into painting the parallels between the cinematic frames and their pictorial references become transparent. Our reproductions stick to the original movie scenes as faithfully as possible without neglecting the obvious characteristics of the medium of painting.

With this approach we suggest a reflection on the symbolic potential of images of apocalypse and their importance for today’s cultural imagery. We seek to link the movie scenes with classical apocalyptic paintings considering not only visual and aesthetic aspects, but also the significance of tradition in the construction of contemporary images. The intention is to put into evidence what modern classics like “Planet of the Apes” (Franklin Schaffner, 1968) or “Independence Day” (Roland Emmerich, 1996) owe to the past. After all, with our history-based analysis of the genre we wish to reveal how any current representation of the end of the world is deeply rooted in tradition.

Kepa Garraza