Miguel Aguirre

Dramatization

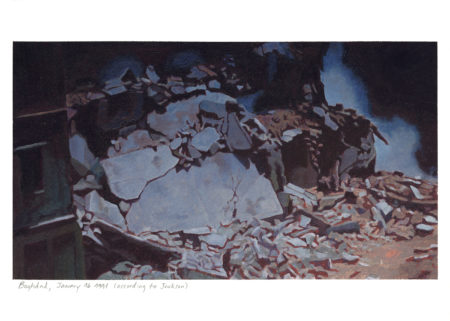

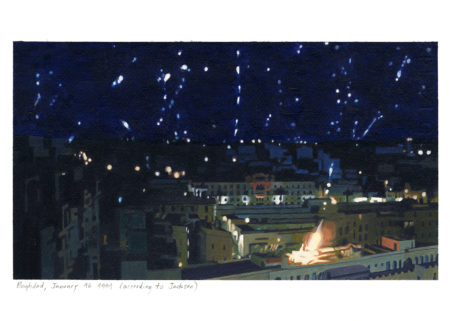

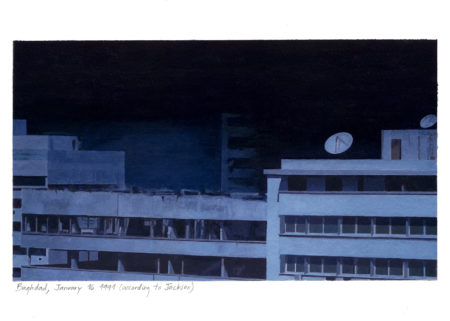

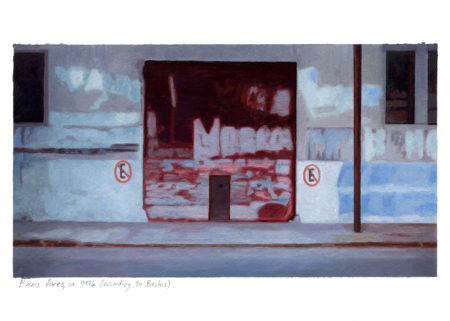

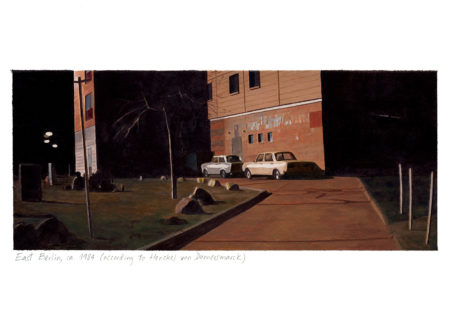

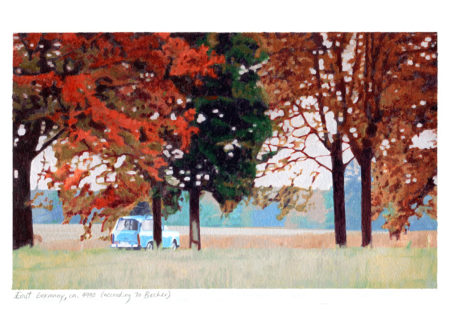

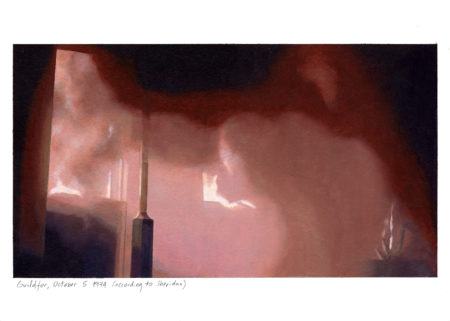

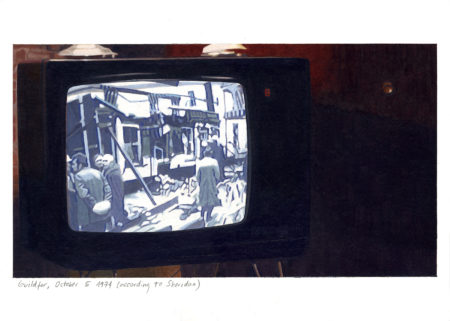

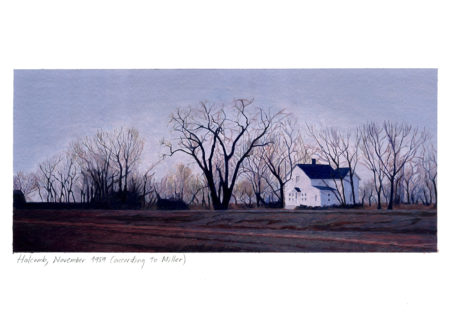

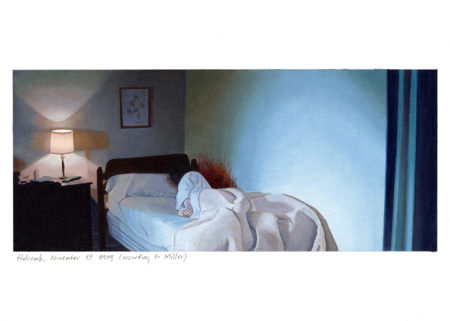

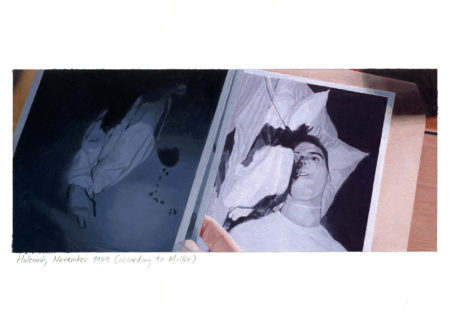

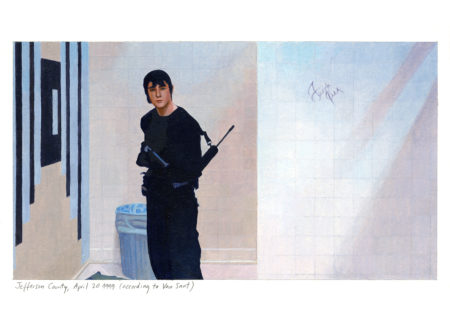

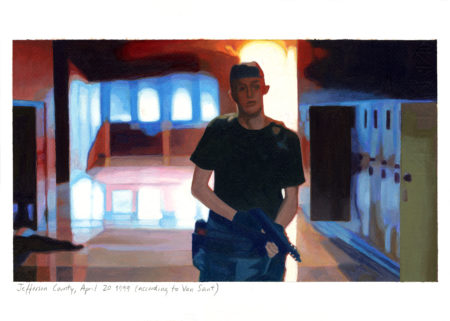

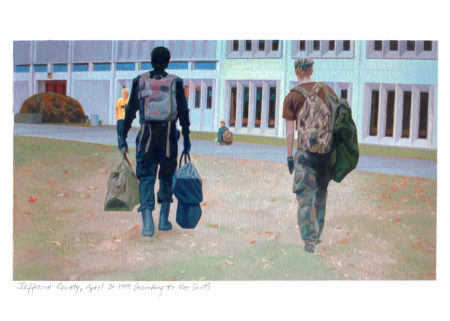

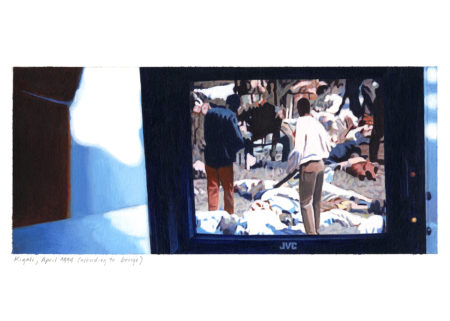

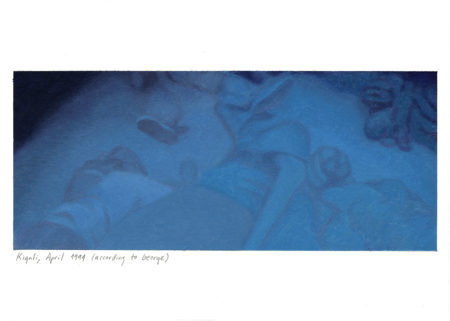

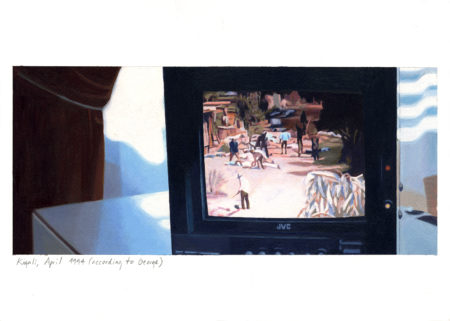

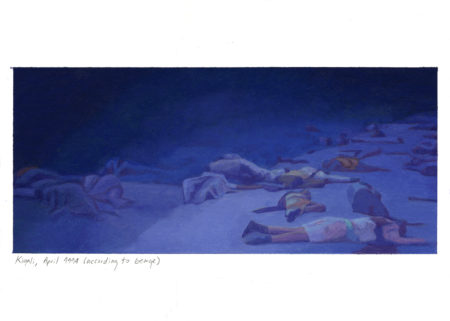

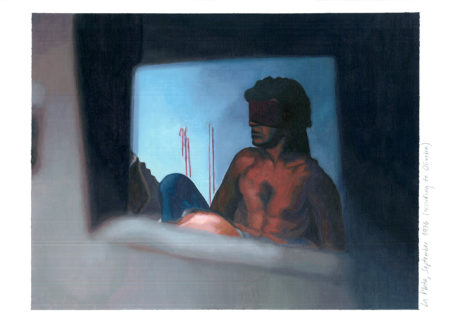

I started working on the Dramatization series towards the end of 2006, when I was in the process of defining a research project. The project was to consist, esentially, in dexcribing, analysing and questioning the objectives and intentions that are pursued in a particular contemporary approach to historical genre painting – making explicit use of models found in images generated both by the media and by cult film directors.

My starting-point was my belief that the pictorial production within a specific group of artists would lead to their adopting a particular perspective; the taking of a standpoint, which would try to subvert the critical lethargy provoked by the indiscriminate consumption of the images projected by the mass media – although, taking their own limitations into account, this very lethargy would necessarily be an intrinsic part of their group too.

I wanted to look at the history painting, as produced in this current century, not as an outdated or descontextualized genre, but instead as an authentic requirement for the visual artist, at a point in history where there is a greater propensity to use other less traditional or more technologically advanced media which appear to be more appropiate. And I would have to put special emphasis on the fact that we obtain most of the information and knowledge about what is going on this world indirectly, not really from direct experience. Most of us are not so much witnesses, as passive spectators of History.

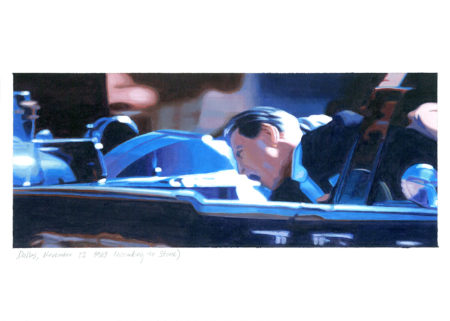

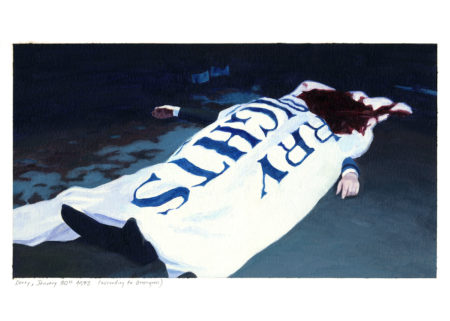

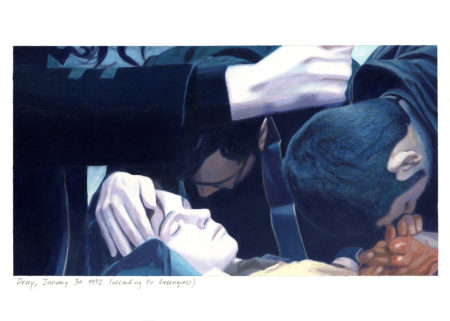

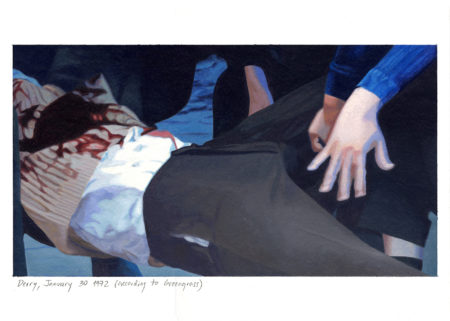

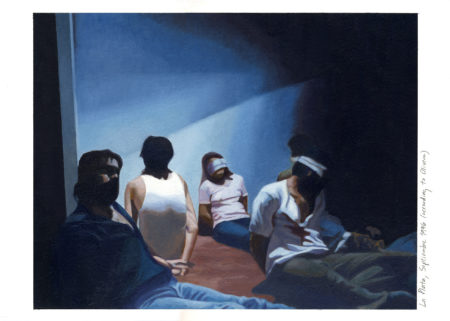

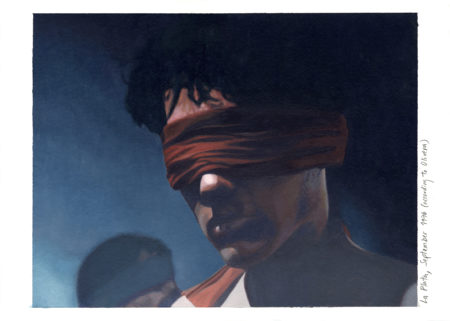

The title Dramatization is a term that I have borrowed from American television series -which I watched assiduosly around the middle of the last decade. In these series, situations of crisis were recreated in minute detail: an accident, a bank robbery or a kidnapping, for example. The sequences of the actual events were inter-cut with the declarations made by the various different protagonists of each dramatic situation.

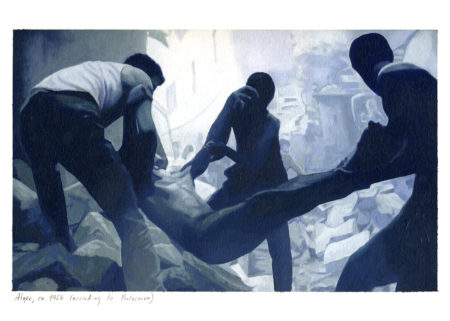

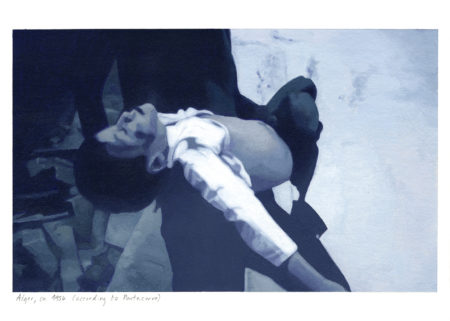

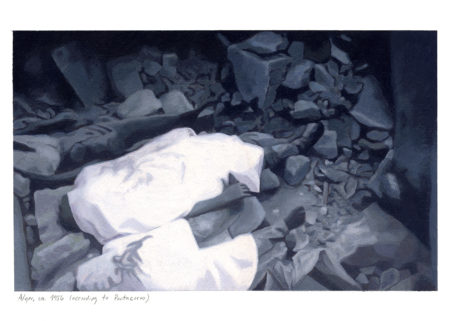

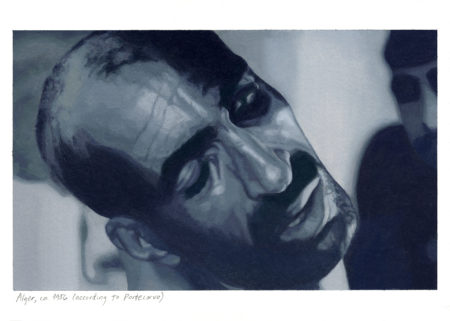

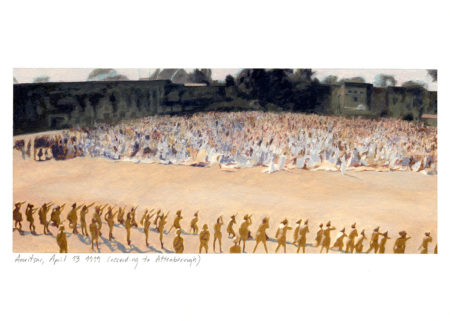

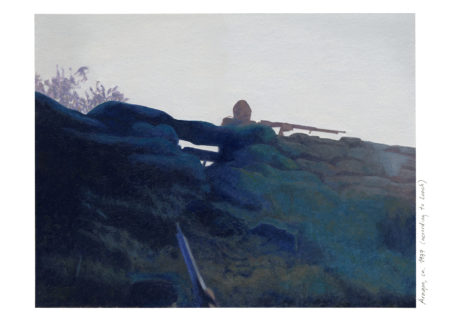

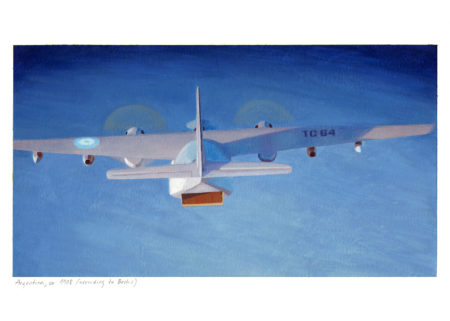

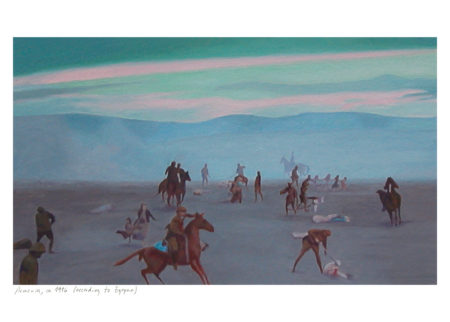

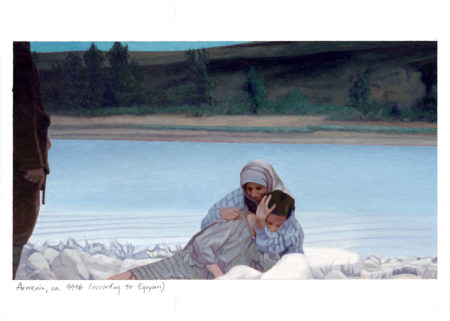

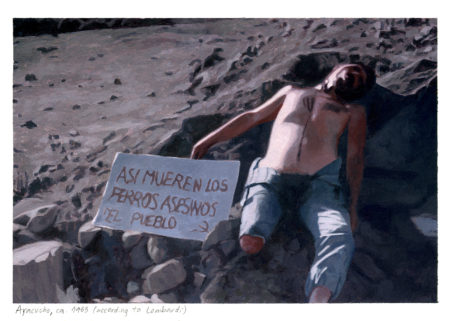

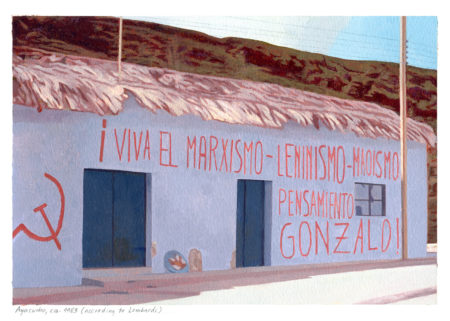

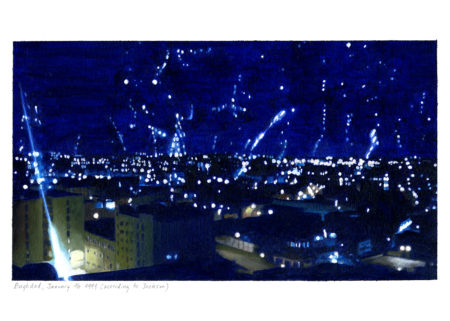

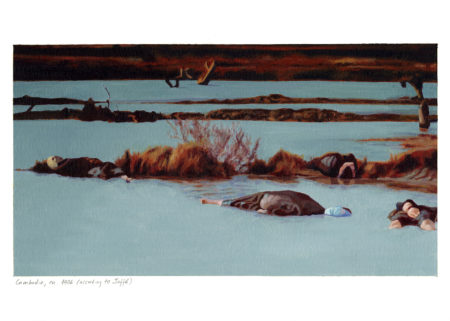

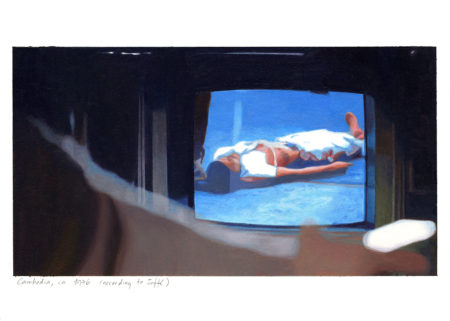

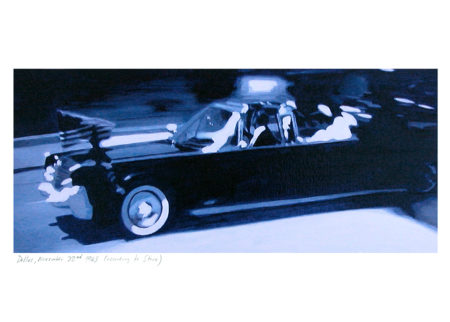

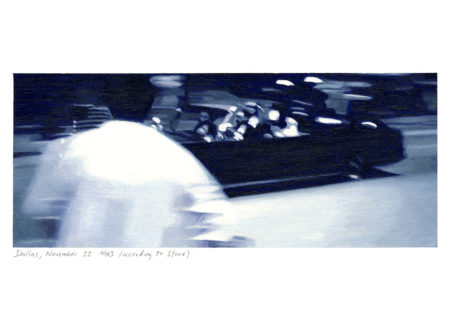

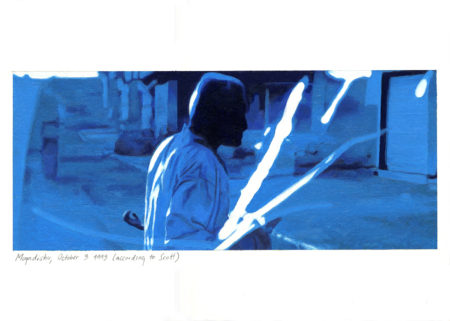

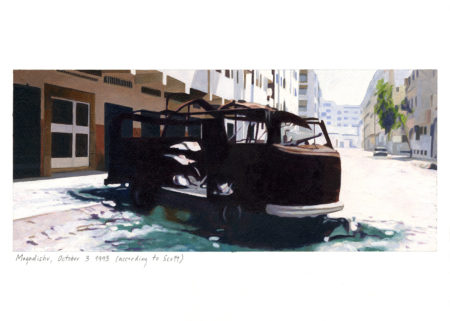

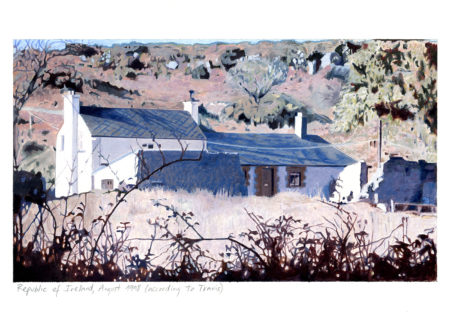

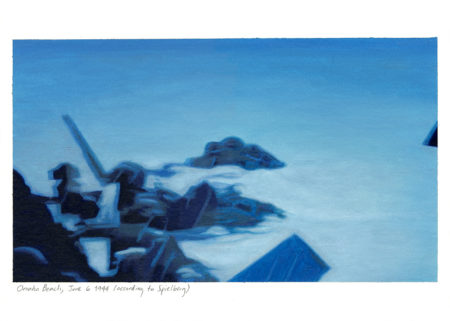

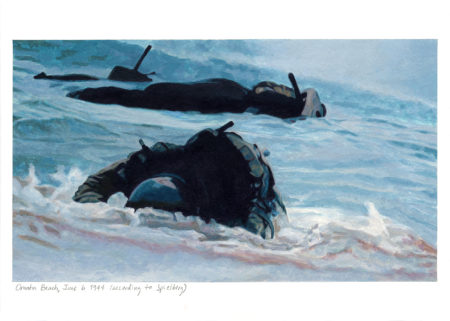

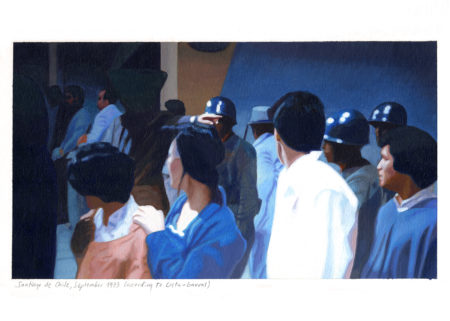

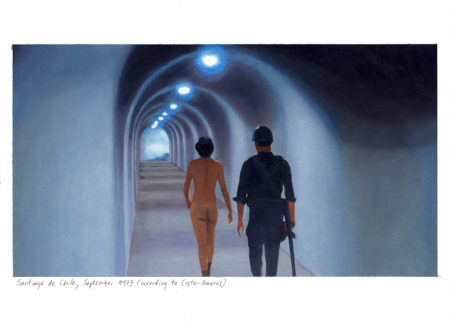

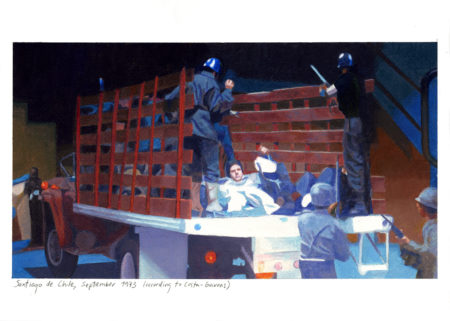

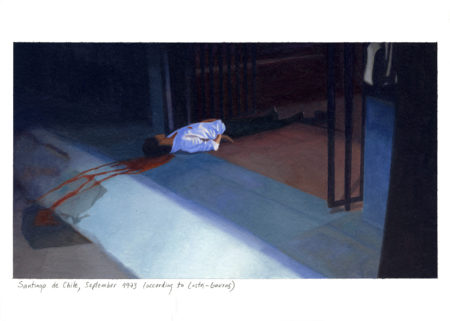

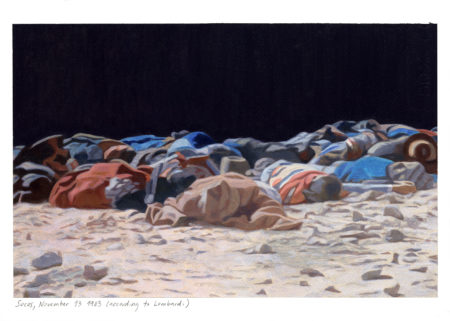

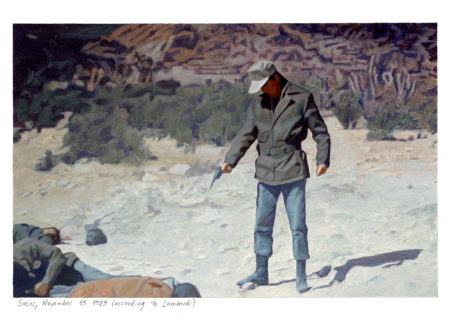

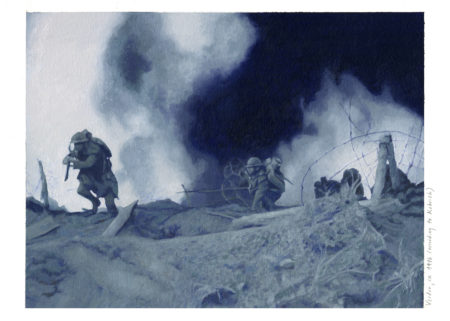

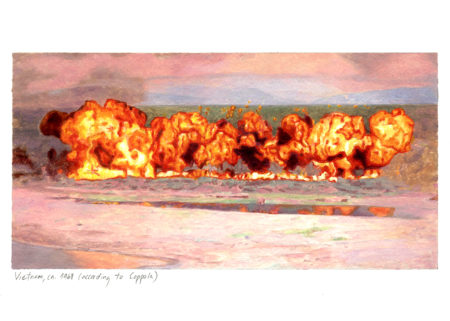

However, in my project I don´t base the pictorial series on facts of a domestic nature. Instead, I use events that have a wider historical effect. To represent these events Imake use of fragments -as if they were still films- that I selected form some twenty or so films, such as La Battaglia di Algeri (1966) by Gillo Pontecorvo, La boca del lobo (1988) by Francisco Lombardi and Land and Freedom (1995) by Ken Loach. Films that -with their accounts of the events in Algeria during the anti-colonial struggle there; the internal struggle in Peru during the 80´s; or the situation on the Aragonese Front during the Spanish Civil War- enabled me to be aware of, or expand my knowledge of, or recollect, events of considerable importance that occurred in the course of the 20th century. In this way, I underline the importance that certain films have, in my view, for the way that we construct our own pinture of the world.

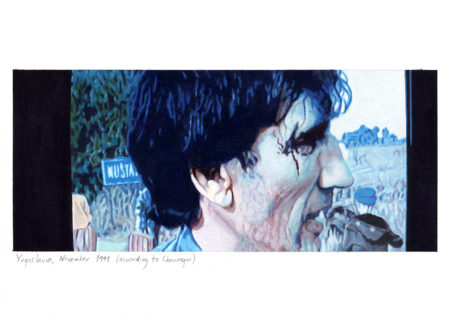

In recreating the murders, and assassinations of world leaders, that have taken place at different times and in different countries, it is the standpoint of the film directors that should emerge. The aim is therefore double: on the one hand, I try to emphasise the attempt by specific film-makers/directors to record and understand their personal experience in relating to events in history -following on from Buchloch, who questions the intentions of the painter of history in the post-modern era- and, on the other hand, I try to pursue the feeling that the spectator has when “re-cognizing” a tragic event, of a certain intellectual and/or spiritual non-conformity.

I started working on the Dramatization series towards the end of 2006, when I was in the process of defining a research project. The project was to consist, esentially, in dexcribing, analysing and questioning the objectives and intentions that are pursued in a particular contemporary approach to historical genre painting – making explicit use of models found in images generated both by the media and by cult film directors.

My starting-point was my belief that the pictorial production within a specific group of artists would lead to their adopting a particular perspective; the taking of a standpoint, which would try to subvert the critical lethargy provoked by the indiscriminate consumption of the images projected by the mass media – although, taking their own limitations into account, this very lethargy would necessarily be an intrinsic part of their group too.

I wanted to look at the history painting, as produced in this current century, not as an outdated or descontextualized genre, but instead as an authentic requirement for the visual artist, at a point in history where there is a greater propensity to use other less traditional or more technologically advanced media which appear to be more appropiate. And I would have to put special emphasis on the fact that we obtain most of the information and knowledge about what is going on this world indirectly, not really from direct experience. Most of us are not so much witnesses, as passive spectators of History.

The title Dramatization is a term that I have borrowed from American television series –which I watched assiduosly around the middle of the last decade. In these series, situations of crisis were recreated in minute detail: an accident, a bank robbery or a kidnapping, for example. The sequences of the actual events were inter-cut with the declarations made by the various different protagonists of each dramatic situation.

However, in my project I don´t base the pictorial series on facts of a domestic nature. Instead, I use events that have a wider historical effect. To represent these events Imake use of fragments -as if they were still films- that I selected form some twenty or so films, such as La Battaglia di Algeri (1966) by Gillo Pontecorvo, La boca del lobo (1988) by Francisco Lombardi and Land and Freedom (1995) by Ken Loach. Films that –with their accounts of the events in Algeria during the anti-colonial struggle there; the internal struggle in Peru during the 80´s; or the situation on the Aragonese Front during the Spanish Civil War- enabled me to be aware of, or expand my knowledge of, or recollect, events of considerable importance that occurred in the course of the 20th century. In this way, I underline the importance that certain films have, in my view, for the way that we construct our own pinture of the world.

In recreating the murders, and assassinations of world leaders, that have taken place at different times and in different countries, it is the standpoint of the film directors that should emerge. The aim is therefore double: on the one hand, I try to emphasise the attempt by specific film-makers/directors to record and understand their personal experience in relating to events in history –following on from Buchloch, who questions the intentions of the painter of history in the post-modern era- and, on the other hand, I try to pursue the feeling that the spectator has when “re-cognizing” a tragic event, of a certain intellectual and/or spiritual non-conformity.