Miguel Aguirre

Build the wall! Build the wall!

In recent months, in Europe and the United States, we have been witness to the clash—social and political, but not ideological—between Islamic fundamentalism and what is coming to be known as post-fascism (a term that, according to the Italian historian Enzo Traverso, distinguishes this new reality from the historical fascism, while suggesting both a continuity and a transformation). On the one hand, the terrorist violence of the self-proclaimed Islamic State or Daesh—whether through trained cells or “lone wolves” who act on their own, taking up the Islamic State’s homicidal discourse—has perpetrated the massacre of civilians in multiple cities (Paris, Brussels, Nice, Istanbul, Orlando); while, on the other, the rise of far-right parties and leaders has spread a populist, xenophobic, and Islamophobic discourse that has seduced more and more people at the ballot box. The immediate solution proposed by far-right politicians involves a reaffirmation of sovereignty, which translates into greater economic, social, and moral control and an identity-based re-entrenchment that is manifested through the expulsion of immigrants, the closing of borders to refugees, and the construction of walls. To hell with do-goodism, a multicultural community, and the idealization of mixed bloodlines. As Traverso notes in his essay “Ghosts of Fascism: Thoughts on the Radical Right in the Twenty-First Century,” democracy in Europe and the United States is not only being threatened from the outside, but it may well be destroyed from the inside. Nationalism, militarism, totalitarian ideologies, terror, and the suppression of all liberties are traits shared by post-fascism and Daesh.

“Build the wall! Build the wall!” is the title of the exhibition project in which different works are used to materialize certain questions that Miguel Aguirre has posed with regard to the current sociopolitical situation in Europe and the United States, specifically the growing democratic support for ultra-nationalist, populist, and xenophobic figures and parties.

In various European countries, this reaction—which ultimately equates to support for populists—is largely the consequence of the refugee crisis and the terrorist attacks carried out by the Islamic State. It is fear and ignorance that cause this behavior. Understanding the causes of this reality, however, is an even more complex exercise, with difficult, and perhaps contradictory, conclusions. One of the sources of this situation can be traced back to a series of actions that were deemed valid, at the time, by the majority of the political class and the media, even though they lacked popular support. It is here that a certain United States administration (that of George W. Bush) can be linked to several European governments (those of Blair, Aznar, and other EU members). We must go back in time fifteen years to talk about what is happening today.

The exhibition will consist of paintings and sculptures. The content of the works is critical, but this message is “moderated” by a formal twist. And sarcasm sometimes comes to the rescue, too, preventing the works from becoming mere political propaganda. The series of small paintings, for example, is literally—and metaphorically—dark (here, Aguirre has made almost no use of white paint), requiring a certain effort to read what is depicted here due to the particular pictorial veil that conceals it. This is his own peculiar series of “black paintings”: eleven images depicting the actions carried out by the government of George W. Bush and his hawks immediately following the attacks of September 11: a war against the Taliban in Afghanistan; the invasion of Iraq, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, and the ensuing absurdities: torture and humiliation at Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, widespread spying under the USA PATRIOT Act, and the emergence of Assange, Snowden, Chelsea Manning, and the WikiLeaks website.

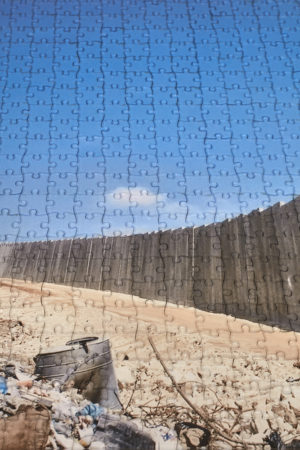

In one piece with a very long title, taken from Eric Fromm’s book Escape from Freedom (“La noticia del bombardeo de una ciudad y la muerte de centenares de personas es seguida o interrumpida, con todo descaro, por un anuncio de propaganda de jabón o vino” (“The Announcement of the Bombing of a City and the Death of Hundreds of People is Shamelessly Followed or Interrupted by an Advertisement for Soap or Wine”)), it is the frosted glass that “softens” (the coexistence of) the informational callousness and the banal advertising in the pages of a Spanish newspaper. Donald´s fun (it´s not funny) is a puzzle consisting of over 730 pieces, with a photo of an enormous wall: a game that represents some very probable and immediate political actions with serious social consequences. In another work, cement and glass shards cover a surfboard. The concepts of freedom (this is how Aguirre views surfing as a sport, in its communion with nature) and security (the glass shards, like the fin of a surfboard, arranged as they were in the olden days on the perimeter walls of Lima’s houses, serve to “protect” the work of art) are paired together and petrified.

On an LED screen, we see a Spanish translation of the meaning of the acronym USA PATRIOT Act. Populisms are experts in the repetition ad nauseam of simple slogans. In this work, the content of the phrase—as if it were a mantra, direct as it is but lacking in precision—is converted into a credo. For many, Bush’s controversial law signified the suspension of human rights and civil liberties in the United States, even being declared unconstitutional. But for more than one, the fact that this law allowed the National Security Agency (NSA) to store data on millions of Americans’ phone calls didn’t matter so long as it helped, in principle, to strengthen the country’s security.

The undervaluation of freedom is the origin of a painting—in appearance, the most pleasant work in the exhibition—in which Aguirre once again creates a self-portrait, fifteen years after the first, in which he is shown holding Fromm’s book. With his back to the spectator, he gazes out at a calm sea in an attitude that is perhaps ambiguous (is he merely observing that great blue flatland from the cliff? Or is he on the verge of making a tragic decision?). This painted performance might serve to summarize part of the concept underlying the exhibition project: freedom and the dilemma in which man finds himself when making use of it, either positively or negatively. The way to be free as an individual is to act spontaneously in one’s self-expression and behavior. When this is combined with solidarity, man is able to fully achieve the highest possible degree of personal satisfaction. He has made positive use of his freedom. According to Fromm, however, the anguish, loneliness, and desperation inherent to modern, industrialized nations may lead him to make negative use of freedom and allow himself to be subdued by a tyrannical system or figure, provided all uncertainty is eliminated and he is able to achieve security. With the promise that the (his) world will “be better.” Could this explain what happened last November 8 in the U.S.A.? Is it thanks to figures like Trump that everything will be “great again”?

Ángel Vega

Lima, November 2016