Miguel Aguirre

(Mal) Archivo

(Mis) Archived

Communicating VesselsOne of the goals of the II Lima Photography Biennial was to manifest the multiple faces of the photographic as cultural production, at different moments and in different environments, associated with an array of purposes in each one of these times and places. Following this line of thought, an exhibition such as Miguel Aguirre’s (Mal) Archivo ((Mis) Archived) occupies a special place in the panorama of the biennial, not only due to the quality of the works presented therein, but also because—from a curatorial perspective—it made it possible to link together two different lines of work.

Under the title of Transformaciones (Transformations), the first of these lines involved a series of exhibits demonstrating the different modes in which photography relates to the real: from the photojournalism of the exhibits of Manuel Moral and the archives of Caretasmagazine, to the vernacular photography of Nicolás Torres, further encompassing an exhibit of the Peruvian photonovel between 1950 and 1980, Manuel González Salazar’s Enciclopedia Gráfica del Perú (Graphic Encyclopedia of Peru), and the panorama of the Latin American Photobook.

The second, entitled Transiciones (Transitions), dealt with certain aspects of the development of art photography in Peru over the last three decades, and included overviews of the work of Luz María Bedoya and Roberto Fantozzi, as well as two group shows: La fotografía después de la fotografía (Photography after Photography) and Cuerpo presente(The Laid Out Body). Photo/Video/Performance. As a whole, these four exhibitions allowed for a highly systematic presentation of the recent changes in the practices of art photography, outlining a panorama of what we refer to as the post-photographic horizon, that is, a broad and varied set of uses of photography with artistic intentions which, in their diversity, go beyond any sort of limits imposed on previous photographic creation, understood in an almost monolithic way based on the specificity and autonomy of the photographic medium.

Within this panorama—through its inclusion in the exhibits that made up Transformaciones(Transformations)—, (Mal) Archivo ((Mis) Archived) acts as a hinge between these two lines of reflection, making it possible to understand both approximations as alternative entry routes into the same reality, that of the current diversity of the photographic and its ability to amalgamate different dimensions of experience.

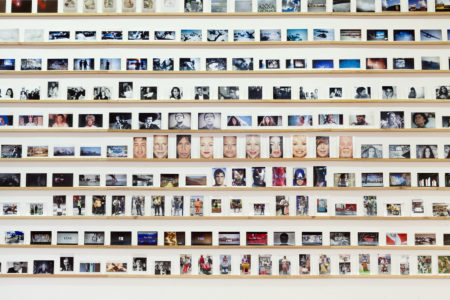

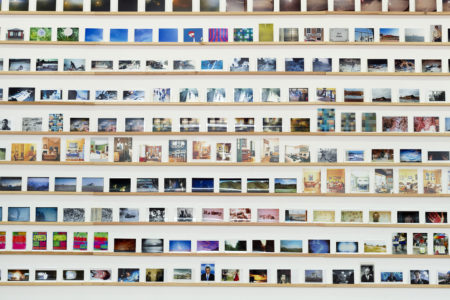

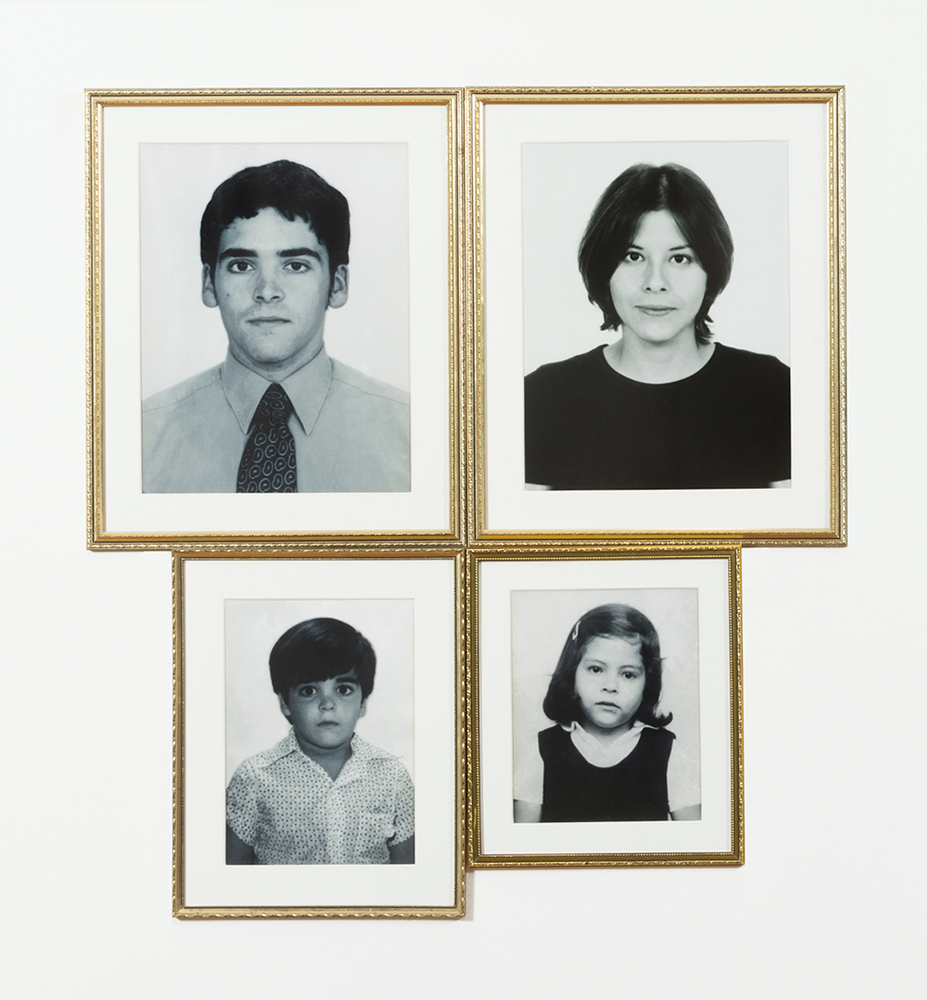

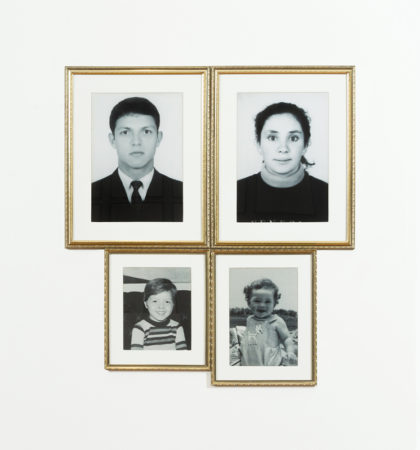

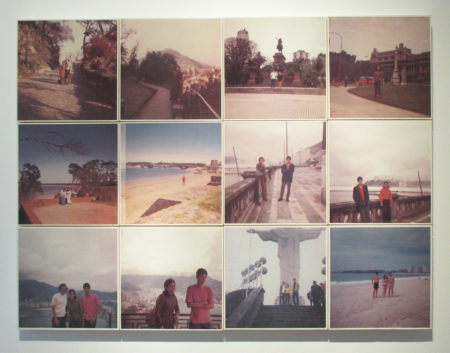

The group of works brought together by Miguel Aguirre in (Mal) Archivo traces its chronological roots back to the series Río, a group of slides sold to tourists in Rio de Janeiro that the artist’s parents bought on their honeymoon in that Brazilian city. Aguirre scanned the images and used Photoshop—pioneering the use of the program in the Lima arts scene of the time—to insert himself, as a sort of guest actor, into the scenes depicted in the slides, thus converting him into a privileged spectator of his own origins.

This act, at once simple and forceful, would not only open for Aguirre a rich vein of exploration and creation; it would also serve to forge links between two areas that, up until then, had practically existed as airtight compartments without any further connections between them: that of artistic practices and that of incidental, homemade photography. With this, he threatened a great many of the precepts of the practice of art photography, leveling the terrain for photographic exploration as an adaptable medium for work of a conceptual nature and for its understanding as cultural production beyond the then-habitual considerations regarding authorship, originality, the aesthetic search, or the compartmentalizing of photographic practice into genres that were assumed to be dissimilar or of differing hierarchies or seriousness. Simply put, a revolution.

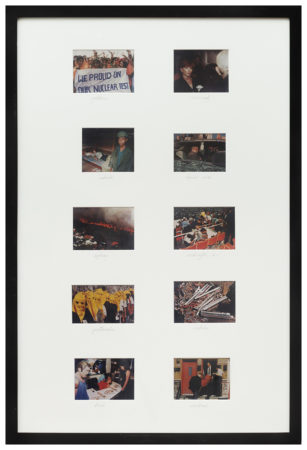

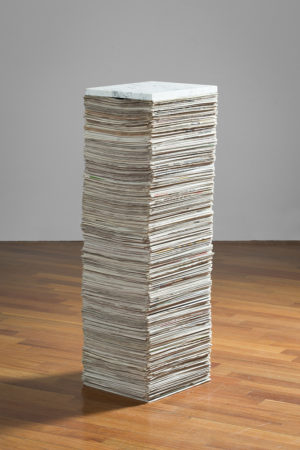

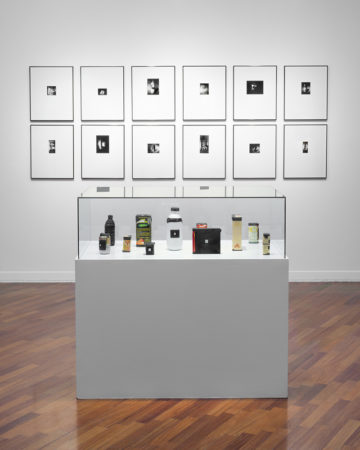

While series such as Luna de miel (Honeymoon) or El buen Fausto (The Good Man Faust), included in (Mal) Archivo, mined the same vein opened by Río, the exhibit includes others of Aguirre’s works that are closely linked through their relationship to the photographic as a medium and/or by their examination of themes similar to those developed in these explorations. Thus, we have here a group of works that—presented as a sort of anthology—share a bond that could be described as that family resemblance which Ludwig Wittgenstein used to describe the relationship between the meanings of natural languages in hisPhilosophical Investigations: that is, not a relationship of category (or categorical relationship), and not a programmatic relationship, but rather a series of visions closely related by a more or less open set of criteria and preoccupations. Much like the semantic fields of natural languages, this (mis) archiving remains open and unconcluded, while at the same time representing a body of work that differentiates itself, as a whole, from Aguirre’s pictorial production and focuses its interest on themes such as the relationship between fiction and reality, inheritance and memory, information, consumption and politics, and, of course, language. Free from painting’s inevitable focus on gesture (and its expressiveweight), the works brought together in (Mal) Archivo make use of the photographic—its relationship, through the very idea of archiving, with the dictionary—to address, as discrete elements of a greater system, different coordinates of modern-day experience, an experience that wavers between the intimate and the high-profile. But, like all semantic fields or archives—both open by their very definition—they also help to comprehend the origins of a large part of Miguel Aguirre’s work as a painter. Because delving into an archive, no matter how limited it may be, is an endless adventure.

Carlo Trivelli

Lima, july 2014