Miguel Aguirre

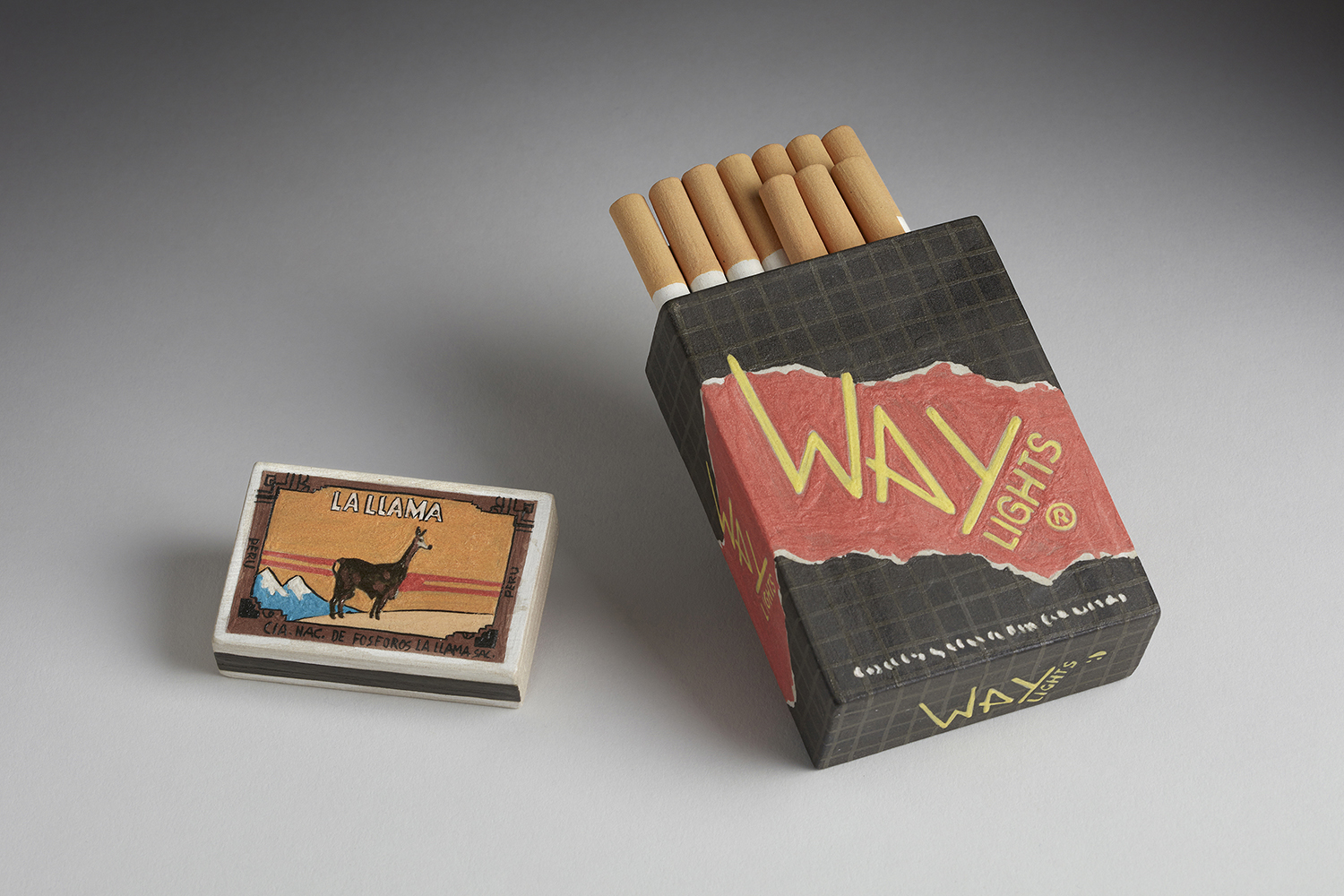

Media cajetilla de cigarrillos y una de fósforos – SLMQG

A Ten-Pack of Cigarettes and a Box of Matches

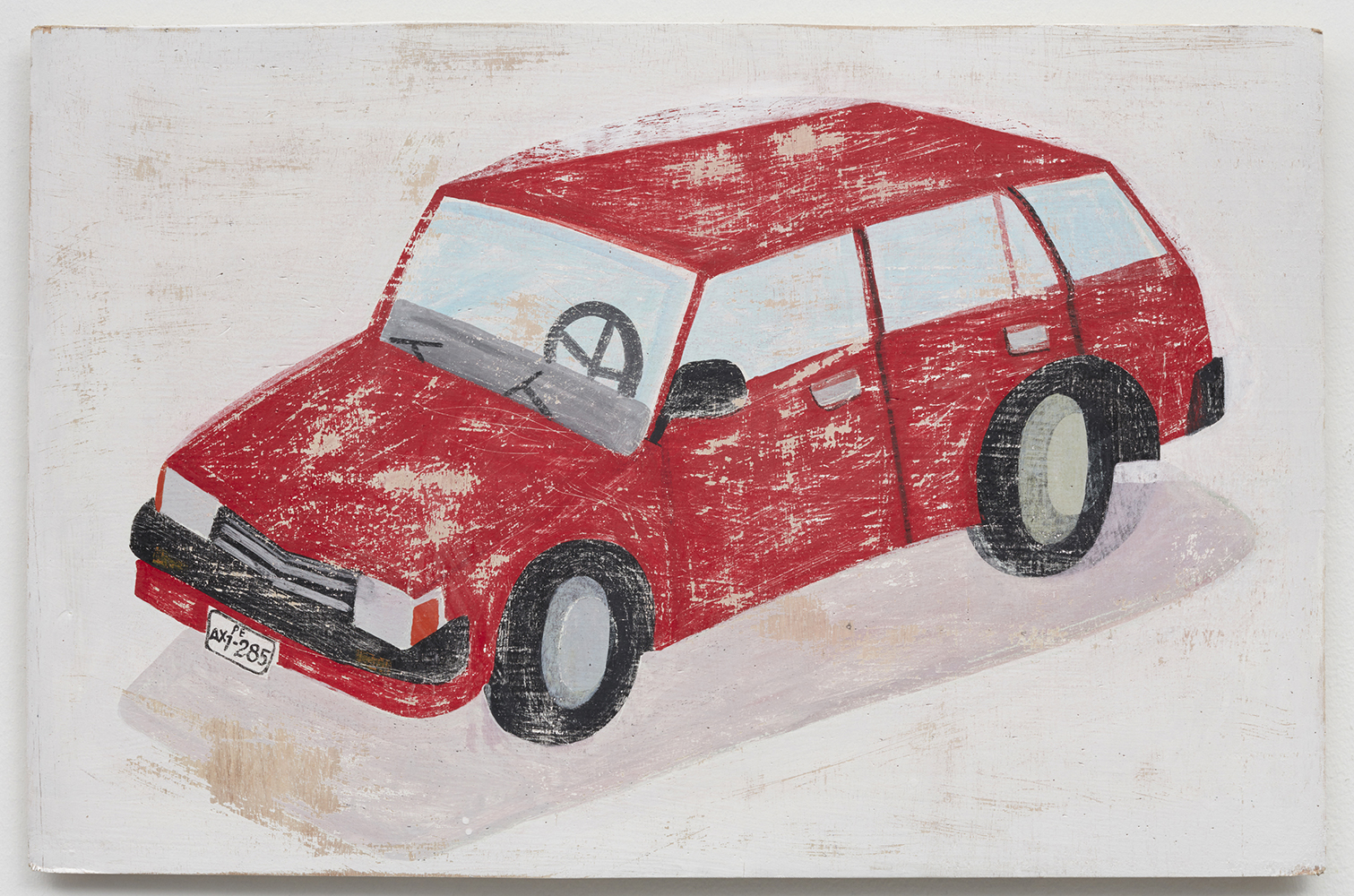

During the first government of Alan García Pérez (1985-1990), inflation skyrocketed in Peru, eventually reaching a cumulative total of 2,178,582%. In other words, prices multiplied 21,785 times over. An article from the journal of the Peruvian Economics Institute explains the phenomenon using a concrete example: In August of 1985, a Peruvian-made Toyota Corona station wagon cost 124,400 Intis (US$ 10,000). In July of 1990, when Alberto Fujimori took office, the same amount of money was only enough to buy a ten-pack of cigarettes and a box of matches (US$ 1.02). This image is both devastating and highly useful in understanding the dimensions of hyperinflation. The inflation process had a disastrous impact on Peruvians’ real levels of income, which was clearly reflected in the significant deterioration in the purchasing power of their salaries and the subsequent economic depression. This event has become part of our country’s collective memory, especially among those of us who lived through those years, under Alan García’s first government and its economic program, which led to the worst economic crisis in Peruvian history.

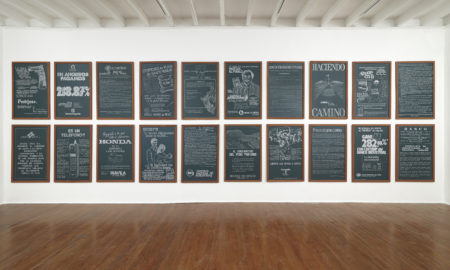

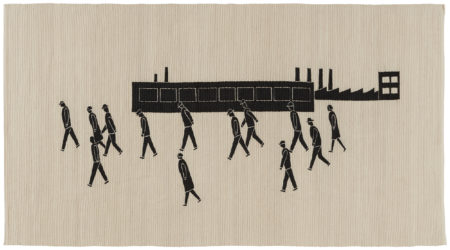

In this exhibition, Miguel Aguirre asks us to relive that time in the Peru of the 1980s, by visually translating a series of details taken from the imaginary found in the advertising, newspapers, magazines, and communiqués of the day involving economic issues or social and political conflicts. This exhibition is heavily autobiographical, reflecting the artist’s adolescence between 1983 and 1992. Among the works on display, we have a group of blackboards, where we observe the reproduction of press materials from that time; a series of ceramic installations that imitate recognizable commercial products from the period; a mural; a textile work; and a video installation.

This group of works aids us in thinking critically, although with an evident sense of humor, regarding many of the events experienced by Peruvians during those years. The artist seeks here to make us remember and rethink that era in politics, in particular. Rather than forging an explicit discourse on the subject matter addressed, the language of the works on display gives each one of us the chance to reconstruct our own memory and the way we connect with that time in our past.

Nicolás Tarnawiecki Chávez

Lima, diciembre de 2015