Miguel Aguirre

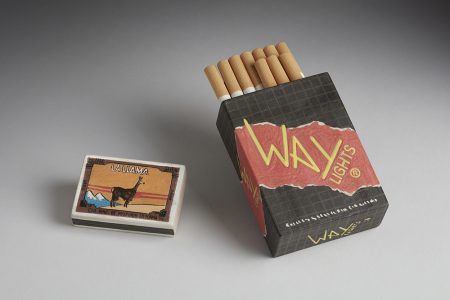

Media cajetilla de cigarrillos y una de fósforos – MUCEN

Rites of passage –those series of demanding tests to which some societies subject males as they emerge from puberty, as a way of publicly marking their transition into adulthood- can be employed in a figurative sense as part of an attempt to identify moments of transition in the experience of men within western society, beginning with the end of infancy. When it comes to the construction of male literary figures, as a discursive resource such rites can also be seen as allusive to the inflection points in the narrative growth structure of the individual.

The application of the tools of literary criticism to the field of the visual arts can be a risky business. But it is tempting, nonetheless, and it is not difficult to see how in the formation of the male character in fiction, as well as in other forms of narrative structure, it can be useful to speak of rites of passage as a way of communicating the significance of the path taken by an adolescent male towards adulthood.

In the structuring of a fictitious memory in a male character, very often the category of “rites of passage” focuses particularly upon a twin initiation: sentimental and sexual, with memories of first love and early sexual experience constituting key aspects of development. In the case of the visual artist Miguel Aguirre (Lima, 1973), it would be very difficult not to associate the conceptual structure he deploys in “Media cajetilla de cigarrillos y una de fósforos” [“Half a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches”] with the opening of a door onto an unwritten cultural history, and to see, at the same time, a form of childhood’s end experience which might be construed as a rite of passage, one which nobody else had taken the trouble to analyze before.

His vision is an innovative examination, in which the overall conceptual strategy is the simultaneous anchoring of memory within two planes: an autobiographical perspective and an unofficial narrative of socio-historic and political history. In this way, Aguirre has managed to introduce very publically a new conceptual program into Peruvian visual art, by addressing with intelligence and honesty the challenge of how to depict a society in crisis, in a past which continues to haunt the memory.

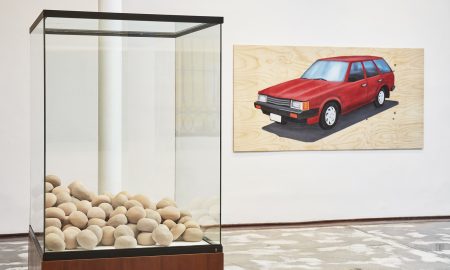

Known and admired as an accomplished painter, in this work he adopts a more contemporary approach, abandoning any attempt to recreate events from the past within that great genre of western academic painting through which historical themes have traditionally been addressed.

It should be remembered that the only painted work in the entire collection is not conceived as an expressive depiction, created with a brush or palette knife in hand. What Aguirre achieves has not been seen before in the art of Peru, because he involves himself in the work as a not-so-tacit first person; in other words, an “I” who is both the narrator and eyewitness of the discernible facts associated with a phenomenon with consequences for the life of the community. And he does this through a material foundation which, in the act of constructing a sensorial quality concocted through recourse to a host of stimuli not usually seen within the Peruvian art of recent times, establishes a refreshing rhetorical revision, presented as ideal through an insightful and irreverent combination of factors. In this way, he provokes a different type of response, communicating directly with the intellect and elemental aesthetic sense of the viewer.

In addition, “Half a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches” offers, through a series of visual constructs, a surprising insight into the social role of the artist and a possible redefining of that role in the field of contemporary art from an apparently simple standpoint; that is, the sudden, early awareness in the life of an individual –still too young to be considered a full citizen- of the existence of something which might be called “economic management”, exercised by a government upon a nation, and which through a series of good or bad decisions –remember, this process should not be seen as one of cause and effect, in any scientific sense- may lead to the crippling of an entire social fabric.

It is not economics as a science which interests Aguirre, but rather its effect upon the individuals who make up the population of a country. To paraphrase the splendid title of the 1970s work by Edward Schumacher, in terms of what is humanly viable within a modern economy, small is beautiful because it allows us at all times to keep in mind that what is most important is people and their happiness; for Schumacher, the only thing that matters, and the only thing that ought to matter, is what we call “the common good”, which includes everyone and therefore should be shared by all. The specific period addressed by the artist and which resonates throughout his work covers the years from 1985 to 1990, a five-year period in the life of the nation during which the country lost sight of what it means to live well, which is not the same as the notion encompassed, with pointed Creole malice, by the expression “the good life”. And to this end, the artist places himself in the landscape through the staging, essentially in chapters, of the memory of those five years of his adolescence, from the ages of twelve to sixteen. In “Half a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches”, he reflects upon and questions the moment in which he began to imagine himself as an artist, the moment from which he could no longer see himself doing anything else in life, which occurred during a phenomenon that radically transformed a historical period lasting just five years. The signaling of the importance of the influence of such a phenomenon upon the personality of the young visual artist enables Aguirre to imagine a way of offering himself in the present as a legitimate social and cultural actor, one capable of taking on the task of soberly dissecting a recent period of republican history, and configuring it through direct allusion to the events that defined the public life of Peruvian society at the time.

The ups and downs of economic and political life go hand-in-hand with the construction of a role for the artist, which this work sets out to articulate in the form of a body of programmatic ideas and a series of artistic pieces clearly conceived for an exhibition space; in this way the artist describes his position as an agent within a creative process that is uniquely his own, in which all decisions appear to be his, while presentations of his work over time appear to serve as chapters in his relationship with the public who follow carefully his career path and output, and who constitute the symbolic community to which he belongs, legitimizing, endorsing, discussing and critiquing his work. “Half a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches” is not merely a staged scene. It also serves to encapsulate obliquely –and not so obliquely- the story of his presence as a producer of symbolic value in Peruvian art.

It may seem strange that it should be Miguel Aguirre, with his highly selective way of creating a pictorial narrative of the body as a wellspring of hormonal signals and physical transformations associated with enjoyment and pleasure as the constituent fantasies of Lima’s petit-bourgeoisie (depictions laden with a healthy dose of narcissism), who has managed to construct a visual chronicle recalling an irreparably fragmented documentary film in the first person, in which social changes brought about by macroeconomic mismanagement are condensed into material milestones which make it possible to see a visit to an art gallery like the MUCEN as an ironic evocation of the Way of the Cross, with the stations on the path translated into a secular language taken from recent historical events: the prolonged economic crisis which culminated in the galloping hyperinflation of 1990. Here, repetition is not laden with a pious ritual sense: as Karl Marx said, history repeats itself, “first as tragedy, the second time as farce”. And it can do so on a huge scale.

To a certain degree, it might be said that “Half a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches” is the B-side -modest and fleeting- of Lugar de la Memoria, la Tolerancia y la Inclusión Social [“Place of Memory, Tolerance and Social Inclusion”], which opened to the Peruvian public in December 2015. The violent history of this country has not been sufficiently processed, assimilated and established at a national level. On the contrary, in spite of its being the irrevocable cultural inheritance of a generation or more of Peruvians, in our own time there have been attempts to repress that history. The effects of murderous violence are not and never can be felt in the same degree by all members of the collective: those directly affected will be marked forever, while the rest of us may only be capable of comprehending such effects intellectually and even then with difficulty. Only in the extent to which each individual’s personal empathy allows it, can we know how to respond in the presence of others, those who walk by our side and who normally we do not seek out or venture to know.

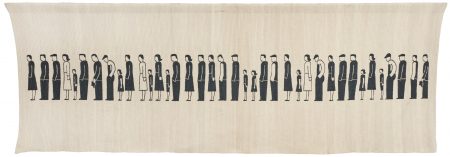

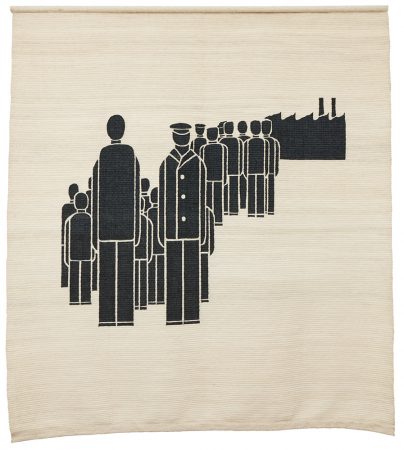

Writing the cultural history of a period in the life of a society is not a challenge that everyone would readily accept or be capable of assuming. It requires equanimity and a self-critical sense, as well as discernment, and also passion. If writing such a history for a period marked by the phenomenon of hyperinflation requires maximum concentration and energy, its transformation into the medium of visual art might easily be dismissed as an enterprise offering very little promise of success. “Half a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches” employs different devices to stimulate visitors. On at least one occasion, Aguirre has invited a contemporary of his to contribute their own piece based upon historical material he has chosen: On the electric guitar, Carlos “Criminal” González plays his own arrangements of advertising jingles from the period. Collaborations are sought both with artists working today, such as the Peruvian Elvia Paucar, from San Pedro de Cajas in Junín, and with artists from the past, as in the case of the socially themed motifs and isotypes which the artist has borrowed and adapted from the work of the designers of Weimar Germany, Augustin Tschinkel and Gerd Arnzt, who worked in Cologne during the late 1920s and early 1930s.

To his range of materials, Aguirre adds a variety of technical media, including weaving with sheep’s wool, the use of commercial paints normally seen in advertising, and video. In one sense, this serves as a reminder of what contemporary artists repeat so insistently today: one should use the technical medium best suited to the intention of the work in progress, whatever that might be.

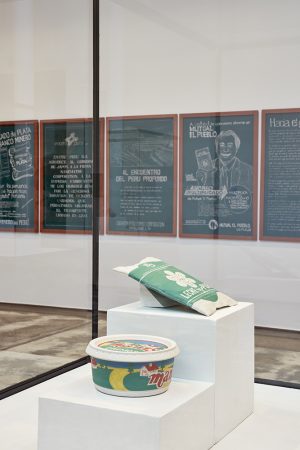

The set of chalkboards is the series which most impresses in this sense. This medium is certainly not normally seen as an artistic one. In this series of twenty-eight identically formatted vertical rectangles, the boards are painted in the same green color typical of the chalkboards that still hang in classrooms in many parts of Peru. But what is written in colored chalk on each of these boards is an advertisement from a company, bank or municipal institution of the period, or a document containing a statement from a labor union or traders’ association. Many of the firms and companies advertised, for example the municipal transport service, have since disappeared entirely and been lost to memory. In monetary terms, the situations portrayed are ludicrous: advertising is rendered meaningless by the terrible devaluation that occurred at the time, and which meant that new currency denominations were required constantly.

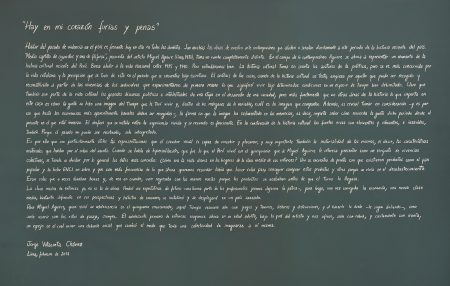

The sensation, relatable to the experience of the classroom, is that at any moment the information may be erased and might not be recovered easily. What is written in chalk is merely transitory, like the words written by a schoolteacher on a board during class. This is the lesson Aguirre sketches out. In this way, the artist issues a warning not devoid of a certain black humor. This didactic tone acquires greater force when one imagines as the protagonist an adolescent schoolboy.

The moment in which a child of school age discovers that notes and coins are worth less and less with each passing day, until they appear to be worth nothing at all, is cataclysmic. Common sense rejects the notion that daily life could be this way, with supermarket shelves emptied of basic foods because of their scarcity, and people having to wait in line for hour after hour in order to buy a single item for domestic consumption. Seeing several members of the same family stand in line, waiting despairingly, and listening to their parents –and to other adults of all ages- asking why they pay taxes and wondering what tomorrow will bring for decent citizens across the country, constitutes a strange experience in terms of knowledge acquisition, bearing little relation to the kind of knowledge normally imparted in elementary and secondary school classrooms.

How can one teach the notion of common good in the crushing presence of unbridled lust for power? Of course, the common good has nothing to do with common sense, although the latter may on occasion serve to remind us of the existence of the former. More than two hundred years ago, in the United States, Thomas Paine observed that, in the best of circumstances, it might be said that common sense is born of limited and particular perspectives which are those of individual existences that coincide in time and correspond, inevitably making them partisan.

It is not easy to remember what the country was like 30 years ago. Miguel Aguirre believes that it is necessary to try, and he has resolved to do so. As a contemporary artist, he subtly and yet firmly suggests that no orchestration of macroeconomic factors should be allowed to become an immovable constellation in a democracy’s sky. Quite simply, the only immovable element should be the political will of a government to serve the entire population of a country.

Jorge Villacorta Chávez

Lima, april 2018