Miguel Aguirre

We are doing fine. I hope you are doing fine, too

The last months have been marked by the division of the gaze into two scopes: in-depth and foreground. In-depth scope has emerged in the few moments in which the horizon could be observed; going out into the street and raising the eyes, valuing social experience under renewed lights, noticing thoughts being traversed by the constant projection of a future to come. However, foreground has prevailed: the sight barely reaching the walls of the domestic interiors during most part of the year, the scarce distance unfolded between the eyes and the screens. The impossibility of looking beyond the immediate, not only in its most literal dimension, has generally prevailed, since the future has been –it still is– uncertain.

Miguel Aguirre’s proposal (Lima, 1973) arises from the dialogue between these short and long gaze scopes, encompassing the artist’s autobiographical and personal experience, as well as the historical and social plane in which it is inscribed; the most intimate and immediate dimension brought about by the experience of the last months and the possibility of observing its consequences with critical distance.

The featured artworks can be understood as the figurative and metaphorical representation of life throughout part of this last year: the distance between bodies, the impossibility of everyday physical contact, the virtualization of labour practices that used to be presential, and the hyperconnectivity through technological devices that now take a central role as a form of socialization.

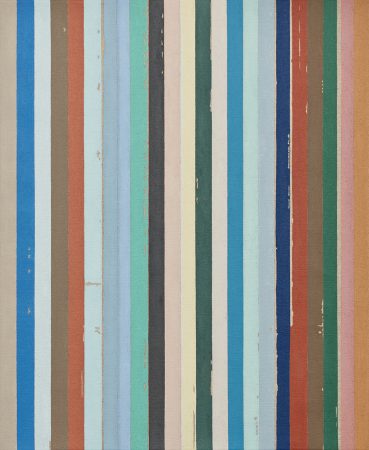

At the beginning of the lockdown imposed on Lima, Aguirre finds through the Instagram platform a way to document the visual dimension of his experience. The extreme close-ups, textures and colours of the indoors are combined with wider shots of the moments when he goes to the streets. On this basis, a series of artworks will emerge to compose a visual diary. The plurality of mediums responds to that logic of trying to give account of a fragmentary experience.

The paintings Día 49 [Day 49], Día 49 (Exagono) [Day 49 (Exagone)] and Día 83 (El jersey de mi padre) [Day 83 (My Father’s Sweater)], which resulted from the artist’s cohabitation with his parents during the first months of confinement, lead to the exploration of a more intimate and familiar dimension of his artistic practise. Similarly, the retablo Día 41 / Día 70 / Día 30 o Los que marcharon [Day 41 / Day 70 / Day 30 or Those who marched], made in collaboration with the artisan Manuel Trini, gives access to the daily life inside a home where the bed sheets hang waiting, as if announcing a time-out.

This set of pieces, far from being merely anecdotal, introduces a disruptive potential into the logic of the art exhibition by making a place for the affective dimension and for the enjoyment of the practice of painting by itself within the critical account of a context such as the present one. In her text Fear of happiness, the poet Louise Glück advocates the importance of making place for pleasant everyday activities as an essential part of the creative process, as opposed to more solemn positions that locate suffering as the source of creativity: “Occasionally something will give pleasure, will actually charm or divert or entertain, will, to use that terrifying word, disarm.”

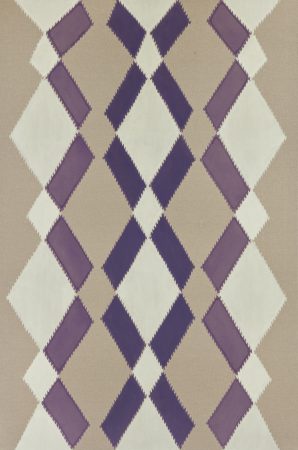

In the triptych composed by the pieces Día 64 / Día 69 / Día 62 o Luna-satélite-anillo [Day 64 / Day 69 / Day 62 or Moon-Satellite-Ring], the three circles are presented as part of the new urban visuality that we find in Lima during the recent months, where the shops and retail establishments mark with paint on the ground the place where the customers should be located in order to keep the required social distance. In this artwork, although that first gesture of looking at the floor confronts us with the rawest reality, at the same time it gives rise to an exercise in abstraction where the gaze recedes and the circles take the form of celestial bodies.

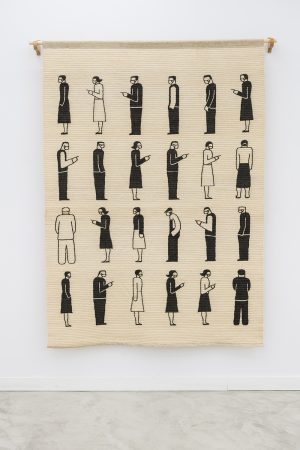

The pieces El martillo y el baile [The Hammer and the Dance], Cola [Queue] and Día 10 [Day 10], woven in collaboration with Elvia Paucar, a craftswoman who inherited the textile tradition of San Pedro de Cajas (at the Junin region in Peru), present images that take as their reference the isotypes of the infographics and diagrams of the artists of figurative Constructivism at the beginning of the avant-gardes of the 20th century. While updating the avant-gardes’ examination of the relationship between the body and spatiality, the fabrics explore, through a simple aesthetic, how body and disposition are arranged when faced with the new situation.

If during the 20th century factory workers were alienated by their labour conditions, today a series of sophisticated ways of modelling behaviour, movements and actions are to be added. In Día 89 [Day 89], Aguirre takes Augustin Tschinkel’s poster as a reference, where the characters praise a plate of food as the great promise for the proletariat, replacing that libidinal locus with Internet and social networks.

The depicted workers are then doubly isolated. Not only physically through the mechanisms of labour control, but also through desire, with their eyes ‘set’ on the promises of the countless images, videos and messages flowing through the networks. In these images, the new dimension that –together with the traditional formulas of exploitation– advanced capitalism brings, has a name of its own. It is not simply a matter of the ‘tyranny of technology’, as it is sometimes generally termed, but rather points to a series of specific agents, which allows us to access a more precise map of contemporary alienation.

The cultural theorist Mark Fisher defends this idea by affirming the need to unmask the fact that capitalism claims for itself the monopoly on the development of technology and desire, understanding the latter as exclusively focused on consumption. Fisher would rather advocate “the construction of an alternative modernity, in which technology, mass production and impersonal systems of management are deployed as part of a refurbished public sphere.” Aguirre’s exhibition unfolds a path towards questioning what the control mechanisms of the present would be, while avoiding falling into nostalgia for a more authentic or real pre-technological past.

Under this logic it is that one can also read the decision to gather art, design and craft in the same proposal. The latter, far from being confined to an idyllic Andean past, breaks with the temporal dimension usually assigned to this milieu and expands its possibilities of being thought of in the present. And this is something that goes in both directions. At the production level, the artworks are made in collaboration with master craftsmen and craftswomen, breaking with the model of authorship and individual creation found in contemporary art and allowing us to imagine new formulas regarding the mediumsthemselves.

Resuming the opening premise, Aguirre’s exhibition moves in a non-linear order between the foreground and the in-depth scope of a lived memory. From its most personal dimension to the acknowledgement of its social and political implications, he captures previously unseen proximities in order to project the gaze towards ultra-present conditions.

Paula Eslaba

Lima, January 2021