Miguel Aguirre

PAROLIBERISMO

In Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s paradigmatic 1914 poem Zang Tumb Tumb typography acquires an expressive and semantic value previously unseen. Through an uncommon use of typefaces and page layouts that give a vivid account of bomb explosions and machine-gun fire and their echoes, the Italian poet and publisher describes the Siege of Adrianople (in present-day Turkey) he had witnessed as a war correspondent one year earlier. He named this technique parole in libertà (words-in-freedom), or paroliberismo.

With the neologism paroliberismo Marinetti consolidates the literary style defined in Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature (1912) and Destruction of Syntax—Imagination without strings—Words-in-Freedom (1913). In these writings he insists on destroying syntax, on abolishing punctuation, adjectives, adverbs and conjunctions, on destroying the I in literature and on using verbs in infinitive. He claims a break with typographical traditions for the benefit of a variety of typefaces and compositions of lines that may be vertical, oblique, circular, surrounded by parentheses or spaced in order to free language from oppressive grammatical, lexical and semantic strings.

The artistic and cultural movement of Futurism as founded by Marinetti was an early, if not the first of avant-garde -isms that inaugurated a profound revision of artistic principles and techniques. Its ground-breaking impact paved the way for artistic movements as revolutionary as Dadaism, Suprematism or Constructivism at the turn of the 20th century and reverberates until today.

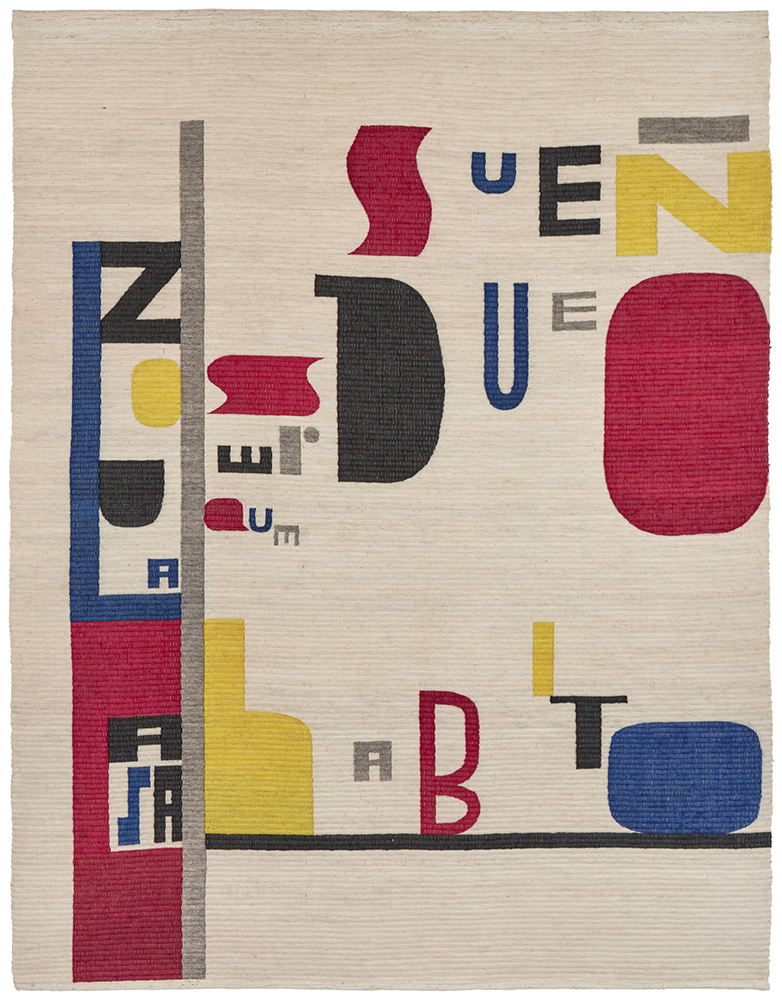

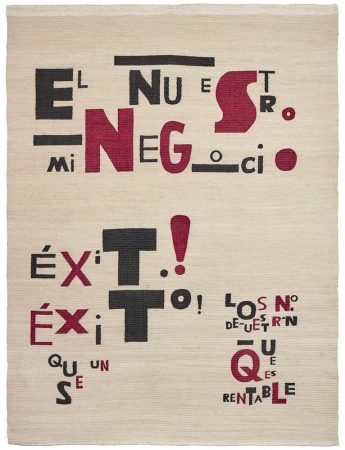

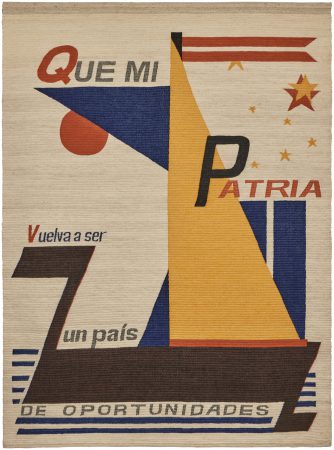

Miguel Aguirre’s new Paroliberismo series opens with two fabrics named SueÑO con Ser DueÑO and EL NueStro Mi NeGocio. For the creation of these pieces of woven tapestry the artist adopts two graphics designed by the Polish avant-garde painter Władysław Strzemiński (1893-1952) for two important compatriot writers under the influence of Futurism and Russian Constructivism: The front covers of Julian Przyboś’ 1930 collection Z ponad. Poezje [From above. Poetry] and Tadeusz Peiper’s 1925 Szósta! Szósta! Utwór teatralny w 2 częściah [Sixth! Sixth! Theater work in 2 parts].

The adaptation of the first cover reads SueÑO con Ser DueÑO / La CAsa Que haBito (I dream of owning / The house I live in), the latter EL NueStro Mi NeGocio / ÉXiTo! ÉXiTO! Que Sea un / LOs Nº demuestRan QUe es renTable (The our my business / Success! Success! May it be / The nos. show It is profitable). Contrary to Marinetti’s initial proposal, these phrases, though slightly difficult to depict, correspond with a correct grammar. The scrupulous respect to Strzemiński’s design reflects in a visual variety of typefaces achieved by alternations in size and color. Aguirre attributes both graphics to the inspirational source of imagined scores where each letter represents a note with its particular tempo and timbre. The phrases can be read quite prosaically as the typical (and topical) yearnings of anybody entangled in today’s neoliberal economy. However, the consideration of Strzemiński’s biography, especially his last years, opens to a rather symbolic interpretation of SueÑO con Ser DueÑO.

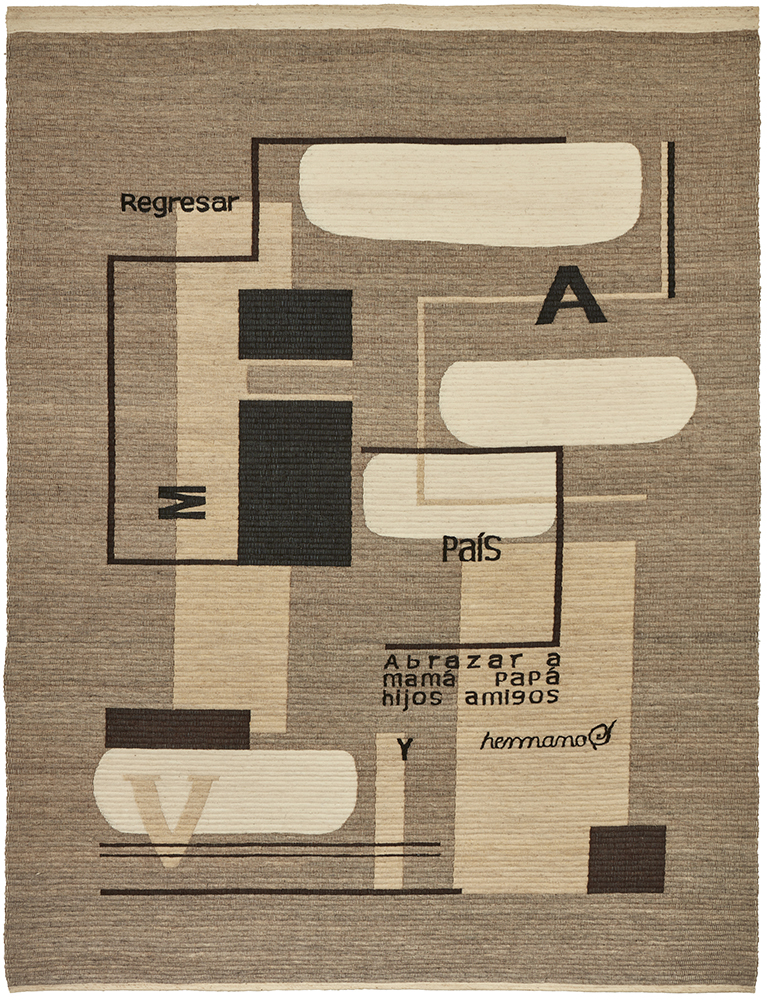

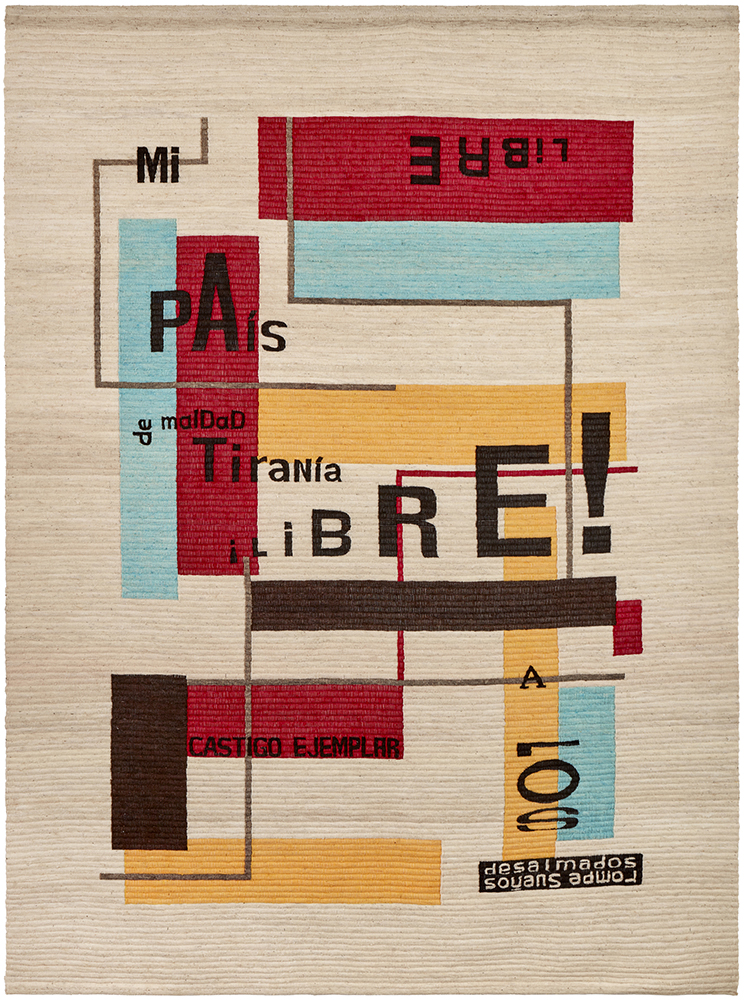

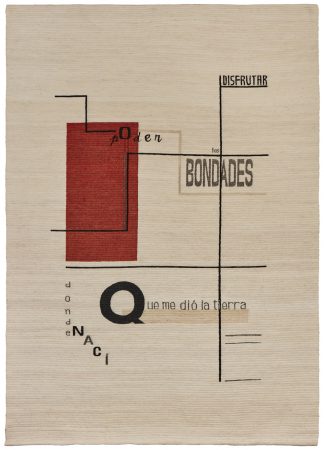

The series furthermore comprises two fabrics that adopt graphics designed by the poet and writer Konstantin Biebl in 1928 and later revised in watercolor by the artist, writer and critic Karel Teige. Both were important active members of modernist avant-garde as well as of pro-Soviet communist groups in Czechia, and both suffered tragic ends in 1951. While Biebl committed suicide under circumstances that remain uncertain, Teige died of a heart attack believed to be triggered by an extremely harsh campaign against him as a so-called “degenerate Trotzkyist”.

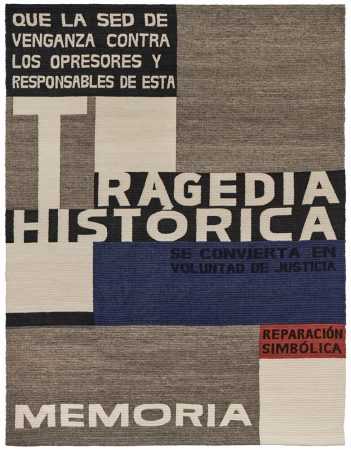

Miguel Aguirre gathers the statements of 25 Venezuelans who, forced to leave their home country due to its delicate political, social and economic situation, installed themselves in Lima (according to the Peruvian migration department, with more than 700,000 Venezuelan migrants Peru is the second receiving country after Colombia). Aguirre asked Venezuelans that form part of his or his family’s everyday network—doormen of their homes, waitresses who serve him lunch, the shop assistant he buys art supplies from, the young barbers who cut his hair—to write down three wishes, however personal or political they might be, that would nourish his artistic work. Two desires recur in each and every statement: the reunion with the beloved ones back in Venezuela, and the complete fall of the regime of Nicolás Maduro. Aguirre condenses the testimonials as follows:

- Regresar a mi país. Abrazar a mamá, papá, hijos, amigos y hermanos (Return to my country. Embrace mom, dad, children, friends and siblings)

- Mi país libre de maldad, tiranía, ¡libre!. Castigo ejemplar a los desalmados rompe sueños (My country free from malice, tyranny, free! Exemplary punishment to the soulless dream-breakers)

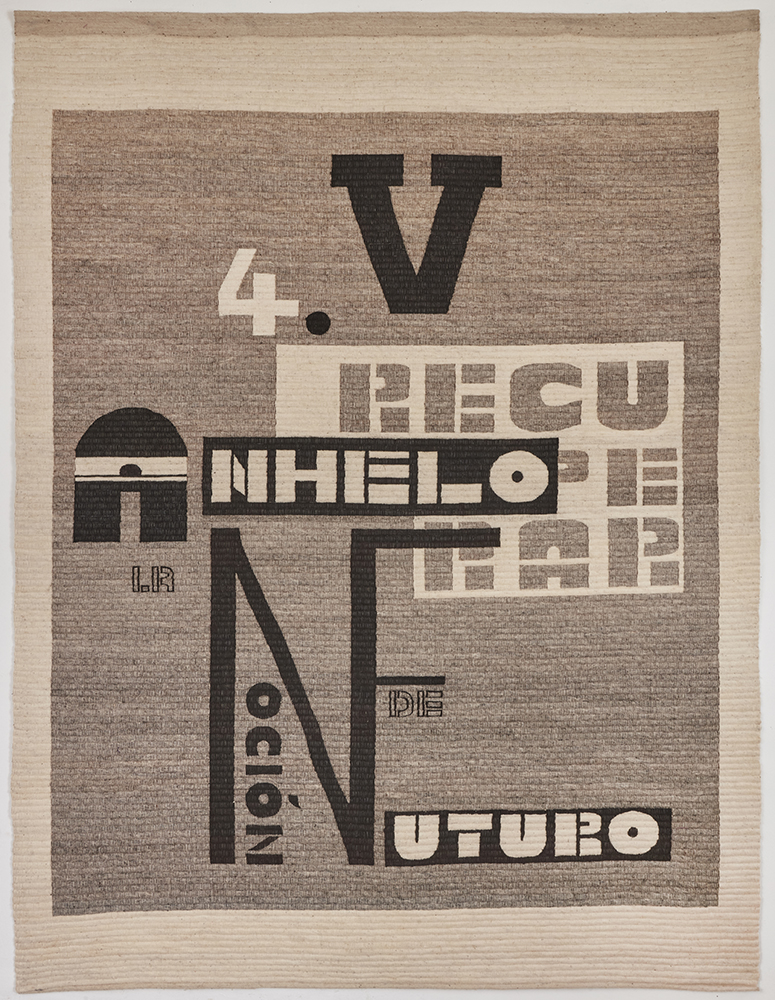

A fifth piece created under the same premises draws on a lithography of the Russian avant-garde artist El Lissitzky (1890-1941) that covered the front page of Berlin-based Broom magazine on February 3, 1923. This fabric named ANHELO RECUPERAR la Noción de FUTURO (a Fabiola Arroyo) (I LONG TO REGAIN the notion of FUTURE (to Fabiola Arroyo)) was created with undyed white, black and grey sheep wool. It features a statement expressed by Fabiola Arroyo, an independent Venezuelan curator based in Lima, which was extracted from her testimony specifically for Miguel Aguirre’s Paroliberismo.